Horizon-scanning: How to plan for alternative business futures

Wilson Wong, Head of Insight and Futures at the CIPD, discusses how to use foresight research for long-term success

Wilson Wong, Head of Insight and Futures at the CIPD, discusses how to use foresight research for long-term success

In this report, we highlighted that the people profession should prioritise horizon-scanning to help inform strategy, collaborating with expertise from outside the profession for a holistic view. As the professional body for HR and people development, the CIPD’s aim is to support the people profession to thrive, now and in the future. This thought-provoking series, with supporting partner Indeed, will curate expert viewpoints from outside the profession, to highlight trends that may shape the future of work for everyone.

In this opening piece, I want to provide an understanding of the significance of futures and foresight in strategic thinking and to debunk the myth that it is too difficult to meaningfully scenario-plan for the future, or that it is merely crystal ball gazing . There is much evidence and data analysed in futures research, used to seek patterns, soft signals of change, pervasive and intractable behaviours and new attitudes and ideas that have the potential to disrupt. However, foresight and futures methods should inform thinking before strategic decisions are made. They identify huge, potentially daunting, issues and considerations within a framework that allows for plans and actions, which expand the perceptions of strategic options open to organisations.

One of the key lessons in futures and foresight is the notion of the human temporal horizon. Cognitively, we tend to overweight the present and underweight the future. An example of this is the slew of articles about the death of the office and how work following the COVID-19 pandemic would be changed forever.

It’s true that some things have changed, but the overweighting of hybrid working discussions is a helpful phenomenon to explore. For example, according to ONS figures in April 2020, approximately a quarter of workers in the UK worked from home. While this was about double the 2019 figures, this reflects a minority that can work from home, even in the depths of a national lockdown. These figures are reflected elsewhere in the world, including Australia, France and the USA. Countries like Japan (that did not impose a nationwide lockdown) did see a rise in homeworking, but it was by no means universal. Remote working is only possible for some jobs, often those in professional and managerial occupations. While the issue of hybrid working is significant, evidentially, this can only affect a minority of workers, but this minority encompasses most decision-makers, who, naturally, address issues closest to their own frame of reference.

Another issue is the time horizon. Most organisations focus on annual and quarterly reporting, making issues immediate and short term. Many pieces in trade media dismiss three-year and five-year plans, regarding these as obsolete in the fast-moving and ever-changing business environment of the twenty-first century. From a futures and foresight perspective, these miss the point; even though the future is uncertain, planning for an uncertain future is still fundamental to resilience. Futures thinking and planning enable organisations to rehearse alternative futures and to react with confidence when elements of these occur.

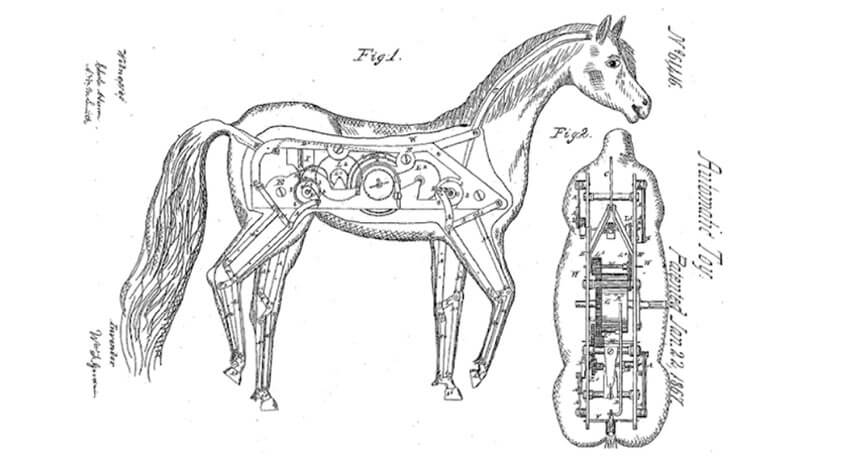

A fun example in illustrating the need to understand how time can alter the frame of reference is the example of the mechanical horse.

This is an 1867 patent for a mechanical horse. It echoes the status quo at that time – how to make the horse more efficient and better able to solve transport and logistical problems. At the time, it was a way of envisioning the horse – a beast of burden, a tool – in its next guise.

While this 1867 patent may seem fanciful, it was human tendency to mimic some of the actions of the real thing, and a way of removing the threatening nature of new technology. What was truly required was the ability to look away from current ‘technology’ – in this case, the horse – and find a different solution to reflect the changing demands of machines. The mechanical horse was designed to address transport and logistics problems, but advancements of the wheel and rail and road networks – a new approach entirely – meant the mechanisation of transport was adequately addressed.

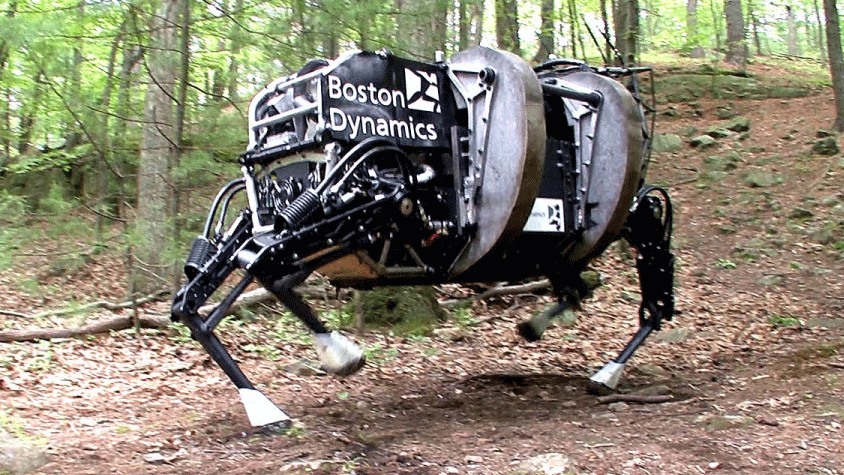

That’s not to say the mechanical horse has no place. In the intervening years, it has reared its head in a variety of guises, such as GE’s walking truck in 1965. In addition, if you look at the latest machines by Boston Dynamics, the robotic horse is very much alive.

This new iteration of the mechanical horse reflects a different question, one of mimicking the seemingly effortless locomotion of humans and animals. The advantage is the deployment of robots to risky and hostile areas of uneven terrain. The confluence of AI and new demands on robotics makes these machines valuable. They work in warzones to remove mines and deal with hazardous areas contaminated with chemicals or radioactivity, on terrain where wheels would be useless.

So, the mechanical horse patent, treated with humour and derision in a different context, is a potential solution to a long-term problem. That 1867 idea has been matched to a need. It just took 150 years.

There are various methodologies in futures and foresight research. My introduction to this began when I supported a scenario-planning workshop led by Shell to look at country-level scenarios, the first instance being that of South Africa envisioning a post-Apartheid future with their Mont Fleur scenarios. We all think about the future but often do not have the data, or the ability to evaluate and analyse it within a framework to answer a need, an eventuality or an issue. Futures and foresight methodologies provide a range of frameworks for making sense of data generated by structured processes to think about a particular aspect of the future. In organisations, these techniques and activities have a particular role in the strategy development process.

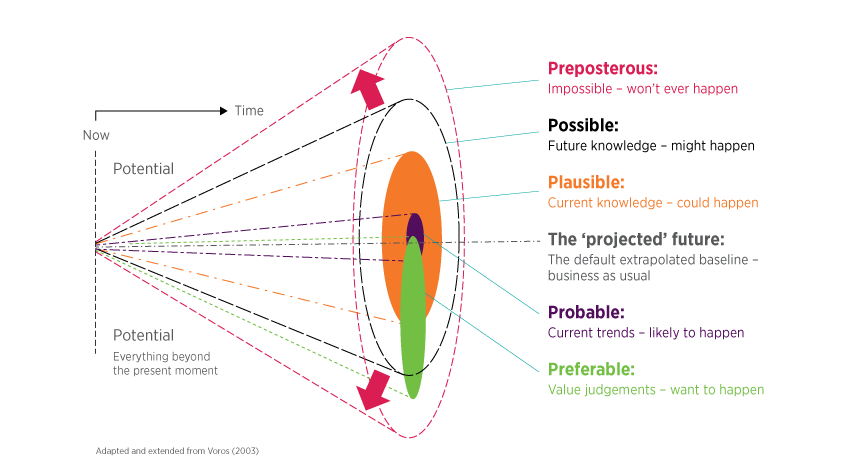

Looking at the futures cone (below), organisations can examine trend data to explore projected futures.

These are futures that are likely in the near or medium term, barring any discontinuities. Some futures and foresight research base predictions on trend data, as these datasets provide plausible trajectories towards a smaller range of futures. Other drivers can upend these trend-based predictions. We could have a major war or a global pandemic which lays waste to risk mitigation strategies that decentralise supply lines, for example. Examples of discontinuities include 9/11, which fundamentally altered notions of terrorism risks and impacted the development of various defensive and offensive technologies and policies that have changed the way we live. Arguably, the COVID-19 pandemic is another discontinuity, although in futures work, the risk of pandemics has been highlighted and rehearsed for many decades.

Organisations will, of course, have their preferred futures, and foresight research can help them to see what factors need to be addressed and contingencies rehearsed for the highest possible chance of success. This may identify potential headwinds, factors that may derail plans and where they can locate convenient and opportunistic tailwinds to further their goals. Part of that discipline is looking at probable, plausible and possible futures as strands that are likely to interact with their plans.

Most would look at strategic decision-making, that is, making choices on what the organisation will do, and then do strategic planning, to articulate the interventions themselves. What is often missed is the precursor – strategic thinking – where leaders examine data feeds organised by various futures frameworks in order to generate and explore options.

One way is to build alternative futures in the form of scenarios, and this is used in two international studies led by the CIPD (The Future of Talent in Singapore 2030 and The Future of Talent in Malaysia 2035). Here we worked with experts in a range of domains and used the Delphi Technique to interrogate and distil key drivers of change affecting the quality and availability of talent in their respective markets. The aim was to provide a futures-thinking resource for policy-makers and corporate leaders to expand their field of vision for alternative future scenarios. In my experience, organisations that focus on status quo planning tend not to thrive in the long run. What seems like a good idea at the present may have very different, and expensive, trade-offs in 10 to 15 years. We only have to look at BP’s forced divestment of their stake in Rosneft following the invasion by Russian forces of Ukraine in 2022.

What makes futures work so interesting and so unpredictable is the behaviour of actors, especially when ably amplified by technology. In practical terms, the quality and rigour of this foresight work depends on resourcing, internal understanding of strategy development and the stability of the business context. My argument is that there are no stable sectors across time. The use of futures in strategy development reflects the maturity and resource level attributed to strategy.

Many issues will be discussed as part of this Future of work thought leadership series – from the challenge of the climate emergency, to the way AI will shape our future workplaces and how societal changes influence how organisations are run. These drivers will all interact with each other for different futures. I, for one, am looking forward to how these will inform my practice as a foresight practitioner. I hope they will also enrich your thinking about options for the future of work and people management.

By Wilson Wong

Browse our A–Z catalogue of information, guidance and resources covering all aspects of people practice.

Discover our practice guidance and recommendations to tackle bullying and harassment in the workplace.

Shaping the future of the people profession through learning with the CIPD

We look at the main focus areas and share practical examples from organisations who are optimising their HR operating model

Our series on current practices, future models and successful transformations

We look at what’s driving change in HR structures, what emerging models look like and what to consider when evolving your current model

How can L&D teams can engage with new technologies like generative AI to impact performance?