Building an evidence-based people profession

We all know that being evidence-based helps us make better decisions, but how can we turn this into a reality?

We all know that being evidence-based helps us make better decisions, but how can we turn this into a reality?

Whether it's drawing up or applying policies, developing managers, or supporting employees, people professionals are often involved in solving complex organisational problems. We need to understand ‘what works’ in people management, but choosing reliable, trustworthy solutions can be a challenge, as there are fads, outdated wisdom and quick fixes to distract us.

This challenge affects all professions and has led to evidence-based practice. The aim is to cut through the 'noise' of opinions to make better informed decisions and help organisations achieve their goals. But how evidence-based is the people profession? And how do we put ourselves on the road to being more evidence-based?

Within the people profession, we face a barrage of often contradictory insights and wild claims about what works in organisations and what doesn't. In addition, every couple of years, large international consulting firms promote a new, cutting edge model or solution that promises to empower your employees and boost your organisation's performance. Especially in a 'post-truth' era:

"We're assaulted with facts, pseudo facts, jibber-jabber, and rumor, all posing as information. Trying to figure out what you need to know and what you can ignore is exhausting."1

As a result, we use mental shortcuts to make decisions.2, 3, 4 These are not just mentally efficient, but necessary to stop our brains from overloading. However, they also mean we are highly prone to biases. Common biases include:

People professionals are often not aware that there is an abundance of scientific evidence available on topics/issues that they encounter in their daily practice5. As a result, people practices in organisations are too often based on tradition, outdated insights or untested 'best practices'.

Drawing on 'best practice' may seem sensible, as we can learn from organisations who face similar issues. However, whereas 'best practice' in medicine means a practice has been shown effective through a large number of rigorous scientific studies, in people management it usually just means 'widely used'. Accepting any practice because it is widely used – without critically evaluating whether the practice is effective and, if so, whether it is also likely to work in a different context – is not a reliable route to effective organisational outcomes.

Likewise, adopting a practice because it was taught to us when we last studied or because it is the way we have always done it, is not a good strategy. Received wisdom may be outdated and new insights may have emerged. Thousands of research articles are published annually on topics that are relevant to people professionals and we should be checking these for new findings and to update our professional knowledge.

Because of confirmation bias, we are inclined to selectively search for information that supports what we want to think, paying less attention to contrary information. In the extreme, 'inconvenient' evidence is wilfully ignored and only evidence that supports our stance is presented: this practice is referred to as 'cherry-picking'. Cherry-picking evidence can make us look smart and well informed, but it is misleading and can have serious negative consequences – risks and opportunities can be overlooked and damaging practices encouraged.

At the CIPD, we believe that being evidence-based is an important step for the people profession, and our Profession Map describes a vision of a profession that is principles-led, evidence-based and outcomes-driven.

The benefits of evidenced-based practice for the people profession are potentially huge. It can lead to the following outcomes:

Being evidence-based does not simply mean backing up one's opinion with a piece of research or data – it is a particular approach to using evidence to inform judgements. 'Evidence' is information, facts or data supporting (or contradicting) a claim, assumption or hypothesis. In HR and management, we get evidence from four main sources (the more of these we can use, the better):

In identifying, analysing and prioritising evidence, we should be:

And finally, the aim is to increase the likelihood of achieving outcomes of interest (for example, increased performance or wellbeing). Evidence-based professionals make better informed decisions by looking at the balance of probabilities, indications and sometimes tentative conclusions. Proof or guarantees are impossible to find.

For more information on what evidence-based practice is and the six practical steps in applying it, see our accompanying guide.

The principles and practices of evidence-based decision-making were first developed in the early 1990s in medicine. Since then, they have successfully been applied in a range of professions, including architecture, agriculture, crime and justice, education, international development, nutrition and social welfare, as well as management.

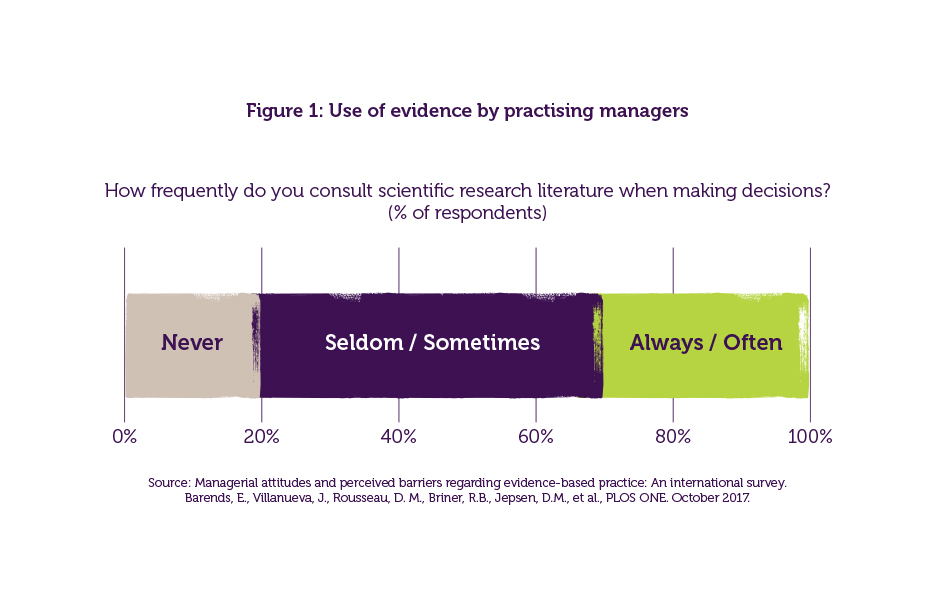

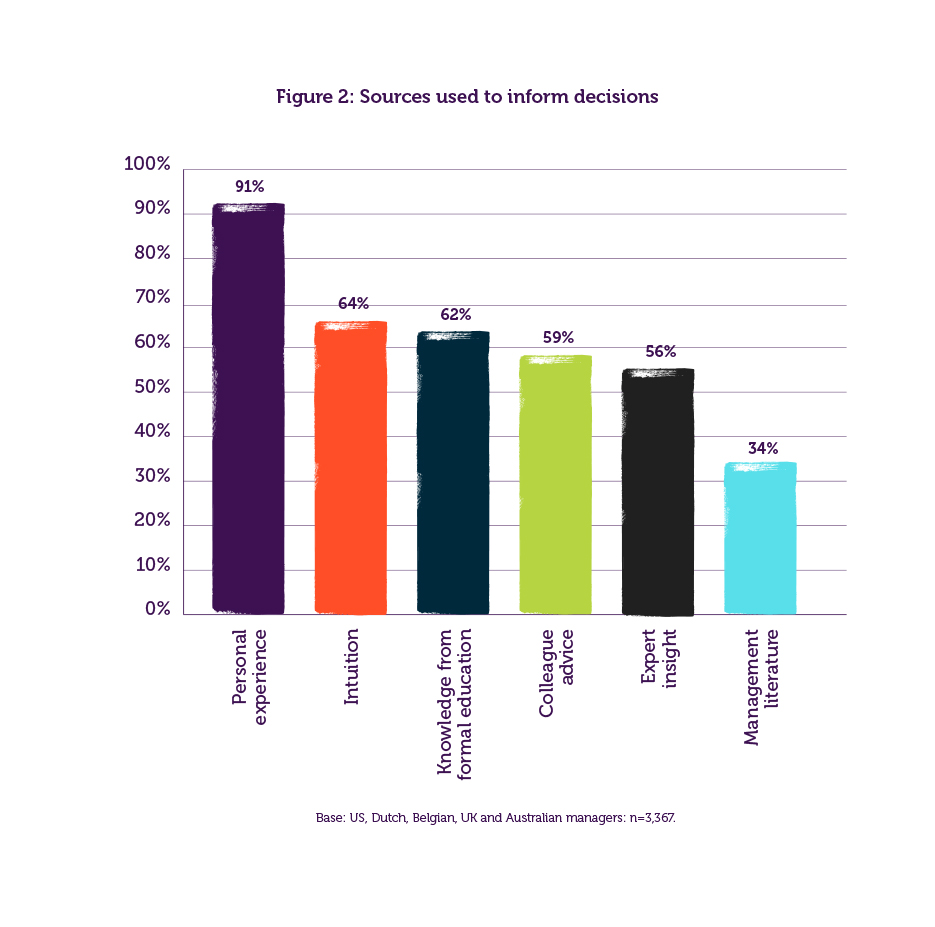

Compared to these other professions, it's fair to say that evidence-based practice is still in its infancy in HR and management. For example, one survey of practising people managers suggests that the majority only seldomly consult scientific literature to make decisions (Figure 1), preferring instead to use sources such as personal experience, intuition and (potentially outdated) knowledge from formal education (see Figure 2).

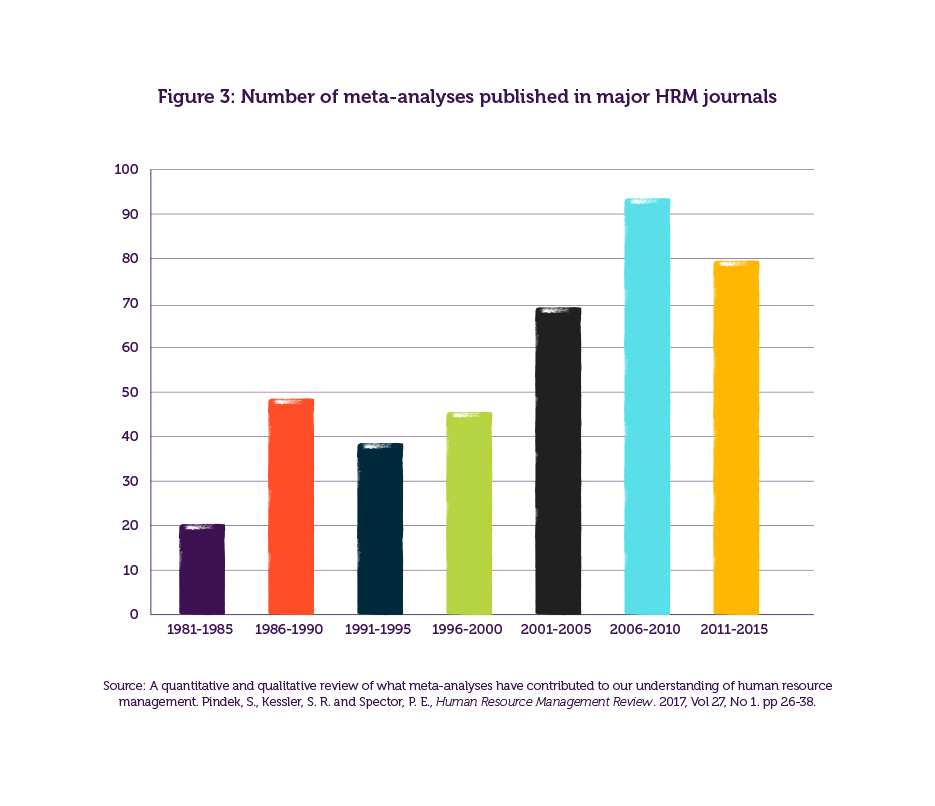

Nevertheless, engagement with robust evidence in HR and related fields has been on the rise in recent years. This can be seen in the increase in systematic reviews and meta-analyses, which contribute to our understanding of HR by aggregating and summarising the body of research on specific topics (see Figure 3).

It may seem daunting at first, and you may find yourself asking: “How do I build evidence-based capacity if I’m not a qualified researcher?” But evidence-based practice is not about trying to turn practitioners into researchers. Rather, it’s about bringing together complementary evidence from different sources, including research and practice. People professionals looking to make evidence-based decisions in practice can begin by following the practical steps in our guide, which are explained with examples and useful questions to ask.

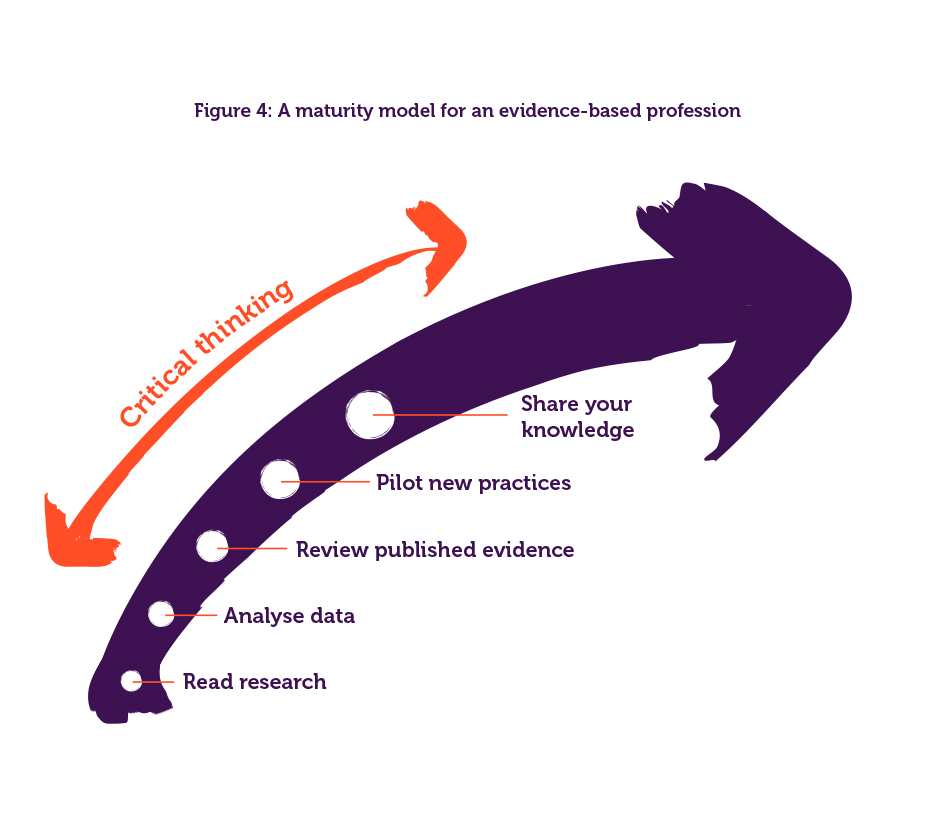

Becoming an evidence-based profession is a challenging aspiration, but people professionals can begin with smaller steps. To help you on your journey, a potential maturity model might look like the one below (Figure 4).

In representing expertise to stakeholders and leading on their specialisms, people professionals can – and should – prioritise the most trustworthy evidence available. The gains in making better decisions on the ground, strengthening the body of knowledge and becoming more trusted and influential are surely worthwhile.

To realise the vision of a people profession that’s genuinely evidence-based, we need to move forward on two fronts:

Becoming a profession worthy of the label ‘evidence-based’ is a long road. We need to chip away over time to see real progress. HR, learning and development, and organisational development are newer to evidence-based practice than other professions, but we can take inspiration from them, for whom it has also been a long road, and be ambitious.

This thought leadership piece was written by Jonny Gifford and Jake Young of the CIPD and Eric Barends of the Center for Evidence-Based Management (CEBMa).

Browse our A–Z catalogue of information, guidance and resources covering all aspects of people practice.

Discover our practice guidance and recommendations to tackle bullying and harassment in the workplace.

A case study on using evidence-based practice to better understand how to support hybrid workforces

A case study on using evidence-based practice to reinvigorate performance management practices

A case study on using evidence-based practice to review selection processes for promoting police officers

A step-by-step approach to using evidence-based practice in your decision-making

We look at the main focus areas and share practical examples from organisations who are optimising their HR operating model

Our series on current practices, future models and successful transformations

We look at what’s driving change in HR structures, what emerging models look like and what to consider when evolving your current model

How can L&D teams can engage with new technologies like generative AI to impact performance?