My working life: Paramedic

Case study from Paramedic, Stuart, on the highs and lows of working life and the different ways that job quality plays out in his experience

Case study from Paramedic, Stuart, on the highs and lows of working life and the different ways that job quality plays out in his experience

'When you’re dispatched to a job, it can be anything from a medical emergency to some sort of traumatic injury. On some jobs you certainly...feel you're making a difference and that you've done something for the patient'.

Job: Paramedic.

Typical hours worked: 50 (five 10 hour shifts, followed by three to four days off).

Profile: Stuart’s in his 40s, is white and lives in the South of England with his wife and family.

After I left university in the early ‘90s, I had no great calling, I didn’t really know what I wanted to do. I ended up working in finance, but I was rubbish, and I couldn’t pass the exams. After two years they told me my future lay elsewhere which I think I’d worked out by that point. I then worked in an office job but when the firm reorganised, I didn't fancy the job I was offered. My wife is a proactive HR type person and she said, 'What do you really want to do?' I said, 'I quite fancy the Ambulance Service'.

When I started there was a role called Ambulance Technician, which was a slightly less involved role than a Paramedic, which I did for nine years. Then I did a diploma for a year which upgraded me to Paramedic in 2009, and that was that. To be honest, I had no real idea what the job was like until I started doing it, but I looked at it and thought, 'Actually that’s somebody who is, potentially, making a difference and doing something useful.' I’ve now been doing it for 21 years.

I’m a frontline Paramedic within the NHS. It’s a rotating shift pattern of 10–hour shifts - all days of the week, all days of the year. They usually run along the lines of two earlies, two lates, and then a night shift, with three or four days off after the night shift, before it starts again. The earliest we start is 6am, the first late shift starts at 2pm and nights are usually 8pm until 6am. Although half of them will be 5pm until 3am. The pattern repeats over 12 weeks but includes three weeks of 'relief' shifts, where you cover people who are off on holidays or off sick, so some of the shifts in those weeks can be anything.

You’ve absolutely no idea what’s going to happen from one minute to the next. When you’re dispatched to a job, it can be anything from a medical emergency to some sort of traumatic injury, mental health or social problem. Even just going round to help somebody up off the floor – for example, an elderly person that’s fallen and is unable to get up. The nice thing is, when you finish at the end of the day you’re done. There’s nothing sitting on your desk waiting for you when you come back in the next morning. You finish and then you leave. You know that patient is not still waiting for you when you come back in at the start of your next shift. You’ve done something, whether that’s take them to hospital, refer them to another healthcare professional. Whatever it is, it’s done, it’s finished, and then you can switch off when you get back home again.

When you’re dispatched to a job, it can be anything from a medical emergency to some sort of traumatic injury. On some jobs you certainly...feel you're making a difference and that you've done something for the patient.

I actually quite like having days off during the week - I certainly wouldn’t go back to doing a Monday to Friday, 9am to 5pm type job. Sometimes the shifts are long. Even at the end of your shift, you have to take a job. If it was triaged as life-threatening, you’d have to go and do it. I never organise anything that starts within two hours of me finishing a shift because I can’t guarantee that I’ll be off at the time I’m supposed to finish. If you're late off, there’s a little bit extra built in to give you a bit more of a turnaround time between the end of one shift and the start of the next. Still, after a night shift, you’re out of circulation because you’re tired. You can’t function, so even if there’re things that need doing at home you either have to risk being absolutely knackered or you just have to say, 'I’m sorry, I can’t pick the kids up from school that day because I need to try to get my rest in.'

The other problem is there’s absolutely no flexibility. There are opportunities to ask if somebody can swap but, because weekends are fairly precious, it’s quite difficult to get the exact time off that you want. There are times it’s definitely been an issue. Next weekend it’s a significant birthday for my wife, and I’m working. I can’t get it off so she’s not happy. Sometimes you miss out on stuff like that. Last week, we were trying to organise something for an hour-and-a-half after I was due to finish my shift and I was late. There’re only so many times you can do that before you feel friends or family think, 'Oh God, here he comes, late again.' Sometimes I think people don’t get that you can’t guarantee your time. I think there were about 30 members of staff and we worked out that there was a total of three of us who were with the same partner/wife/husband that we were with when we started doing the job. The vast majority of people, within five years, split up because it does put a strain on relationships because of the shifts and everything else.

I think it’s a good job. Quite often at work we say our job is actually easy. I suppose it’s no different from any other job. If you’re in the job and you like it and you’re suited to it and you enjoy it, it seems easy. I’ve never once come back off holiday or after a run of days off and, that first morning when the alarm goes off at 5am, thought, 'I don’t want to get up, I can’t be bothered to go in today.' I’ve never ever thought that. I just enjoy it. I like the unpredictability – it’s nice just to come in and not quite know what you’re going to do. I enjoy just being out and about, not being stuck in one place. It can also be incredibly interesting hearing people’s backstories. The patient is different every time so there’re never two jobs that are exactly the same. For a lot of the time, you can work at your own pace. There are targets of how long we are supposed to spend on scene on each job, but you’re not constrained by that. You spend the time you need to with each patient.

On some jobs you certainly do feel you’re making a difference and that you’ve done something for the patient, whether that be in terms of sorting out their pain or getting them to the correct place for ongoing care or sorting out a social problem or whatever. But as I’ve been in the job longer, I’ve often realised there are certain times when I’m not going to make a difference and there’s nothing I can do about that. That’s just the way the system works or that’s just the way that patient is. You know – it doesn’t matter what you do. I think, as I’ve got a bit older and wiser, I’m better at just shrugging my shoulders and saying, 'That’s just the way it is' and not letting it get to me.

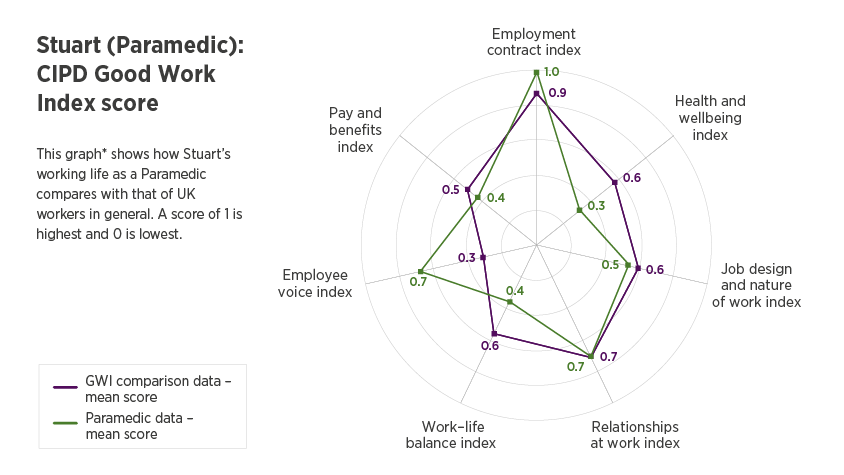

*This graph shows Stuart's score alongside the UK mean (average) for the 7 dimensions of the CIPD Good Work Index.

I'd say I’m relatively well paid for what I do. Yes, there are slight downsides in terms of the shifts and everything else, but it just suits me. At my level of experience, I’m at the maximum on the scale – I’m earning just under £50,000 a year. I’ve got a fairly secure pension and I’ve got a relatively decent amount of holiday. Sometimes getting the holiday when you want can be difficult but in terms of the package it’s pretty good. I’m never worried about being made redundant. But… a newly qualified Paramedic is only earning just over £30,000 and that’s not good enough because they’re doing exactly the same job. There’s no difference. They’re still expected to perform the exact same tasks and it takes about eight or nine years to reach the top of the pay scale.

I think the job certainly means you feel tired, and it does affect your physical health because sometimes your body clock or eating times are thrown out. On those 6am starts, my official lunchtime is 9:30am. If I get my lunch then, I’m still working until 4pm in the afternoon so you’ve got a big gap (possibly between 9:30/10:00am and after 4pm, when you don’t have an official break). Sometimes that encourages you to snack or eat unhealthily. On a night shift, you know, who wants to sit down and eat a big meal at midnight? Yes, it’s a bit odd. From a mental health point, I sometimes feel a little bit embarrassed or guilty or whatever that I can’t commit to things on a day I’m working. I’ve not had a day off sick in about 12 years. So it’s obviously not affecting my health that much, but then that’s part of me – I hate taking time off, I’d rather be at work.

I’ve not had a day off sick in about 12 years. So it’s obviously not affecting my health that much, but then that’s part of me – I hate taking time off, I’d rather be at work.

There are opportunities to move up. There's a new role called a Specialist Paramedic, who they’ve given some more skills to like minor wound closure, a little bit of prescribing and stuff like catheters, which we never used to do. That means going back to do a part-time university course. There’s quite a lot of detailed anatomy and physiology involved, quite a lot of underpinning knowledge. My brain doesn’t work that way, I can’t retain that sort of detailed information. The other part of their rotation is act as a Clinician within the 111 service – they’re sat behind a desk on a phone for hours on end which is definitely not me.

Another option is to develop the management side as a Team Leader, who is a Paramedic. They do shifts on the road, but they then tend to get more involved in management rather than actual patient issues.

If you move up, it takes you away from the patient which is why I want to be doing the job in the first place. I’m quite happy. If I was ever to do a job which took me away from the patients, the frontline, I think I would regret it.

I’m based at one station, and we work in teams. Within my station there’re four of us who always work together. It’s set up as two clinicians, paramedics, and two non-clinicians called emergency care assistants.

As the Clinician, you have ultimate responsibility. Anything they do, it’s your responsibility. If they make a mistake it, technically, comes back on me because I’m supposed to be supervising what they do, and they’re supposed to ask me before they do anything. There’s certainly that level of trust with somebody who you know you can leave them to get on and do that and they’ll come back and tell you if there’s an issue or a problem and then you can sort it out. When I’m at work, I’m spending more time with my work colleagues than I am at home – it’s a close relationship. I like the people that I work with. I enjoy the banter on station.

We have a Team Leader who oversees us - a sort of management role. He’s based at another station, so I very rarely see him but he’s always available on the phone. We’ve got a good relationship and I get on well with him. Once it goes above that sort of level of management, we very rarely see them or have anything to do with them. It used to be the joke that you’d panic if you turned up and saw a white car parked outside, because that meant a manager was on station and that somebody was in trouble. If you saw two white cars, you knew somebody was in big trouble because there was a witness to what was ever going on. It’s one of these things where your direct line manager and you have a relationship and speak reasonably regularly. Once it goes above that, it’s distant and you have absolutely nothing to do with them unless you’re in trouble.

Most of us are fairly open and honest with each other. It tends to be the sort of job where you do voice your opinions. If you think somebody is not pulling their weight or making mistakes, because we’re dealing with people’s lives, we sometimes can be a little bit blunt with each other. But I think we all accept that. I’ve rarely known anyone become offended by anything someone has ever said.

I’ve always got the impression that if somebody who sits at a higher management level has come up with an idea, then they certainly don’t like to be criticised. If your boss said, 'This is a great idea', if you want to keep your job you agree with your boss and tell him it’s a great idea. If I went to them with an idea, yes, I think possibly I would be listened to. Sometimes managers blame the system. I’ve known colleagues who’ve gone and suggested things and the manager has said, 'Yes, that’s a really good idea but that’s not the way things work.' In management positions, you tend to reapply for your job every three years. I think sometimes people are wary about doing anything, particularly towards the end of those three years, that might jeopardise any chance they have of being retained in their position.

To do this job, you need to have a reasonable amount of patience and certain interpersonal skills. You need to be able to talk to people, you need to be able to listen and to take in quite a lot of information. If somebody is telling you either their symptoms or their previous medical history, you have to be able to process that fairly quickly and retain it. So you don’t end up asking them the same question half a dozen times. You also need to be fairly resilient because sometimes you do walk into some fairly shocking situations. I don’t mean blood and gore, I mean sometimes you walk into some social situations when you think, 'Oh my God, how does anybody live in this sort of squalor?' for want of a better word. I've dealt with a lot of calls where there was substance abuse and poverty. You can be in a mansion one minute and a council flat the next. You need a very good sense of humour sometimes as well. I think the only sacrifice really, is the shifts. I’ve also made that conscious decision not to progress into management roles within the Trust because I know that’s not the sort of work I want to do.

It’s the sort of job that definitely changes you, it becomes a massive part of you. My wife has often joked that she’d never ask me to choose between her and the job because she knows she’d lose. It’s probably true because I couldn’t think of me doing anything else. I can’t think of another job that I’d rather do. We used to joke that there’d always be somebody sat in the corner - it was usually a middle-aged bloke, which I’ve now become - who used to sit and moan and moan about the job and how much it had changed. Then you asked him how long he’d worked there, and he’d say 25 years. You think, 'It can’t be that bad.'

Tackling barriers to work today whilst creating inclusive workplaces of tomorrow.

Discover our practice guidance and recommendations to tackle bullying and harassment in the workplace.

Explore the many rewards of working in the people profession

Explore career areas within the people profession, and the typical activities you may find yourself doing

Information and guidance to help you excel in your role, transition into the profession, and manage a career break

If you’re looking for a career in HR, L&D or any other aspect of the people profession, there’s a route that’ll suit you

What are the barriers that stand in the way of achieving 'good work', and which need to be addressed as a priority?

Listen nowA Northern Ireland summary of the CIPD Good Work Index 2024 survey report