Impact of performance management on employees

Mark Beatson discusses the different types of performance management and why they are important

Mark Beatson discusses the different types of performance management and why they are important

Managing employee performance is central to the jobs of most people managers. Knowledge and understanding of performance management is part of the CIPD Profession Map. Yet performance management can seem as much art as science. Judging by our website data, people want to know more – mainly the ‘nuts and bolts’ but also about the evidence, especially ‘what works’ and why.

To take the discussion further, we look at the impact of performance management on the performance, health and wellbeing of employees, based on a survey of 5,000 people, in work that underpinned the CIPD Good Work Index 2023.

In 2022, we added questions to the survey asking employees how their performance was managed. Data for 2023 showed that nearly half (48%) had at least a basic level of performance management, namely that specific objectives were set for their job (Figure 1). In most cases where objectives were set, employees thought management monitored their performance against these objectives and gave them feedback on the extent to which they had been achieved.

Figure 1: Different types of performance management (UK, excluding self-employed, owner/proprietors and partners in a business)

Note that the questions did not specify how these steps were undertaken. Performance management could be formal (written down, with standard procedures) or informal (through the questions that people managers put to employees).

Source: CIPD UK Working Lives survey 2023

Just over a quarter (28%) of employees had ‘systematic performance management’, namely with elements we might recognise from an HR textbook:

Employees reporting systematic performance management were more likely to rate their performance positively than employees with no performance management (Figure 2). For example, 76% of employees with no performance management agreed that “I achieve the objectives of the job, fulfil all requirements” whereas this figure was 89% for those with systematic performance management.

Figure 2: Impact of types of performance management on task performance (UK, excluding self-employed, owner/proprietors and partners in a business)

Note: Totals do not sum to 100% because the proportions replying ‘don’t know’ are not reported.

Source: CIPD UK Working Lives survey 2023

The increase in positive outcomes was greatest when feedback became part of performance management, a finding consistent with existing evidence.

Similar results (not reported here) were found for the effect of systematic performance management on other measures of employee performance, physical and mental health, and job satisfaction.

Another CIPD report The importance of people management: Analysis of its impact on employees, showed how line manager quality affected employee outcomes. For example, 50% of employees with bottom-quartile managers thought work had a negative (or very negative) impact on their mental health, compared with 14% of employees with top-quartile managers.

Performance management goes hand in hand with good people management (Figure 3). Employees subject to performance management that included an element of dialogue (those with feedback and/or accountability) rated their managers more highly on average than employees with more rudimentary arrangements or with no performance management.

Source: CIPD/YouGov UK Working Lives survey 2023

Of course, there are various ways this relationship could work. Good managers could ensure systematic performance management takes place by ensuring the right questions are asked and that employees are given an opportunity for dialogue. Alternatively, systematic performance management arrangements could improve the quality of line managers, or the relationship could be due to other factors such as the training of managers.

Just over one-fifth (21%) of employees thought their pay was affected by the achievement of objectives (Figure 4). Even where objectives were not set, 11% of employees thought their pay was affected by their performance, which sounds counter-intuitive, but employees may be thinking of bonuses, commission or piecework. Where performance management was systematic, a majority still did not recognise any link to their pay.

Figure 4: Likelihood of performance-related pay (PRP) by type of performance management (UK, excluding self-employed, owner/proprietors and partners in a business)

Source: CIPD/YouGov UK Working Lives survey 2023.

While the existence of systematic performance management is associated with superior task performance, there seems to be no difference between those with performance-related pay (PRP) and those without PRP, implying the marginal impact of PRP was negligible (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Impact of performance-related pay (PRP) on task performance (UK, excluding self-employed, owner/proprietors and partners in a business)

Note: Totals do not sum to 100% because the proportions replying ‘don’t know’ are not reported.

Source: CIPD/YouGov UK Working Lives survey 2023

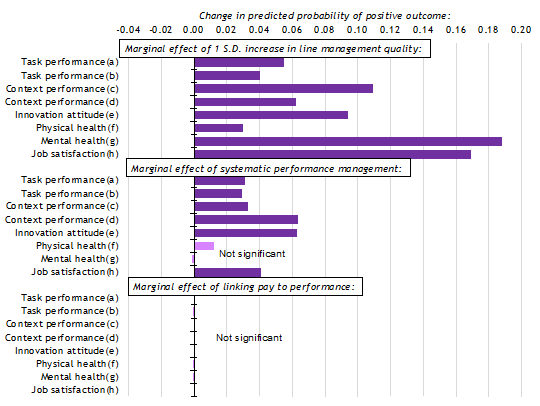

Finally, we look at the relative effects on employee outcomes of three different changes:

The relative impact of these changes was modelled using regression analysis that allowed for both personal characteristics (such as age and sex) and job-related characteristics (such as industry and occupation). Technical details are in the notes to Figure 6.

Figure 6: Relative impact of line manager quality, performance management and performance-related pay (UK, excluding self-employed, owner/proprietors and partners in a business)

(a) Agree/strongly agree that “I achieve the objectives of the job, fulfil all the requirements”. Dependent variable in ordered logit regression with personal controls (sex, age, ethnicity, disability) and job-related controls (full-time/part-time, sector, size of organisation, industry, occupation, job tenure, managerial status), line manager quality, presence of systematic performance management and presence of PRP (n=4040, pseudo R2=0.034).

(b) Agree/strongly agree that “I am competent in all areas of the job, handle tasks with proficiency”. Dependent variable in ordered logit regression with personal controls and job-related controls), line manager quality, presence of systematic performance management and presence of PRP (n=4072, pseudo R2=0.027).

(c) Agree/strongly agree that “I volunteer to do things not formally required by the job”. Dependent variable in ordered logit regression with personal controls, job-related controls, line manager quality, presence of systematic performance management and presence of PRP (n=4062, pseudo R2=0.050).

(d) Agree/strongly agree that “I help others when their workload increases (assist others until they get over the hurdles)”. Dependent variable in ordered logit regression with personal controls, job-related controls), line manager quality, presence of systematic performance management and presence of PRP (n=4057, pseudo R2=0.045).

(e) Agree/strongly agree that “I make innovative suggestions to improve the overall quality of my team or department”. Dependent variable in ordered logit regression with personal controls, job-related controls), line manager quality, presence of systematic performance management and presence of PRP (n=4029, pseudo R2=0.068).

(f) Positively/very positively in response to “To what extent does your work positively or negatively affect your physical health?” Dependent variable in ordered logit regression with personal controls, job-related controls, line manager quality, presence of systematic performance management and presence of PRP (n=4027, pseudo R2=0.047).

(g) Positively/very positively in response to “To what extent does your work positively or negatively affect your mental health?” Dependent variable in ordered logit regression with personal controls, job-related controls), line manager quality, presence of systematic performance management and presence of PRP (n=4018, pseudo R2=0.099).

(h) Satisfied/very satisfied with main job. Dependent variable in ordered logit regression with personal controls, job-related controls, line manager quality, presence of systematic performance management and presence of PRP (n=4092, pseudo R2=0.126).

Source: CIPD/YouGov UK Working Lives survey 2023

The single largest improvement in employee outcomes would result from better people management. This is consistent with our recent report on productivity, which highlighted the contribution made where manager training was widespread. Systematic performance management usually has a significant, though lesser impact. But adding on PRP would seem to make very little difference.

Browse our A–Z catalogue of information, guidance and resources covering all aspects of people practice.

Discover our practice guidance and recommendations to tackle bullying and harassment in the workplace.

Mark's respected labour market analysis and commentary strengthens the CIPD’s ability to lead thinking and influence policy making across the whole spectrum of people management and workplace issues.

Prior to joining the CIPD, Mark was an economic consultant and for over 20 years worked as an economist in the Civil Service, latterly at Chief Economist/Director level, in a range of Government departments including the Department for Business Innovation and Skills (BIS), the Department for Innovation, Universities and Skills (DIUS), the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) and HM Treasury.

This research outlines recommendations for making feedback discussions more constructive

Understand the basics of performance reviews and how to ensure the process adds value to the organisation

Understand how to build an effective approach to performance management, including the tools that can support it

Examines the history, principles and current practice around competence and competency frameworks

Monthly round-up of changes in employment law in the UK

Research on how an employee's socioeconomic background or class affects their development opportunities and how to maximise social mobility in the workplace

We look at the main focus areas and share practical examples from organisations who are optimising their HR operating model

Ben Willmott explores the new Labour Government strategies to enhance skills and employment to boost economic growth