What monitoring measures are acceptable when managing remote workers?

An investigation of employers’ perspectives on monitoring remote workers

An investigation of employers’ perspectives on monitoring remote workers

A growth in hybrid working means bosses with hybrid teams, who previously only managed people onsite, would also need to learn how to manage remote workers. Their organisation’s productivity and culture are at risk if their people can’t adapt to connecting and collaborating when they’re not physically in the same space. Attempts to monitor those working remotely might backfire if people feel it’s unnecessary or intrusive.

So, what do bosses think are acceptable ways of managing workers who work remotely, particularly those working on laptops or other electronic devices? What is practised in various organisations? Are there differences in opinion by management level, industry and so on? These are some of the questions that we explored in the CIPD’s Technology, the Workplace and People Management Survey 2022, conducted in partnership with HiBob.

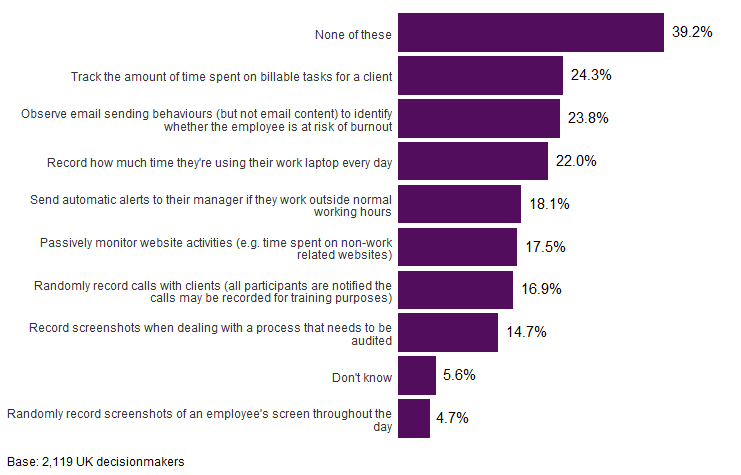

We asked bosses who responded to our survey to select examples of methods they felt were acceptable for collecting information about employees working from home, whether on their laptops or electronic devices (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Which are acceptable ways of collecting information about home workers who regularly work on a laptop or other electronic device?

The data showed a spectrum of opinion. At first glance, it appears the largest proportion (39.2%) felt that none of the measures were acceptable, while 5.6% said they didn’t know.

However, over half (55.3%) agreed with at least one of the eight measures in Figure 1, despite not having a strong preference for a particular example (Figure 2). Even when asked to think specifically about employees working from home on laptops, bosses were divided.

Figure 2: Over half of bosses agreed with at least one of eight measures

This is because context matters. What’s the employee’s job? Is an audit trail essential? What’s the cultural norm in the organisation? For an accountant, it may be the norm to track their billable time for clients when they’re in the office, so the same would likely apply when they work from home.

The three most accepted measures (selected by 44.8% of respondents) relate to how much time employees spend on their laptops and identifying risk of burnout. Some bosses seemed keen to mirror existing practices in the office for employees working from home. It’s possible that some see recording time spent on laptops as a replacement for using key cards to track attendance in the office.

The three least accepted measures relate to recording screenshots and randomly recording activities. Bosses are uncomfortable with the idea of randomly collecting more information than they need to assess their employees’ performance or wellbeing. Screenshots can capture more personal data than is needed for audit, a potential liability for the organisation.

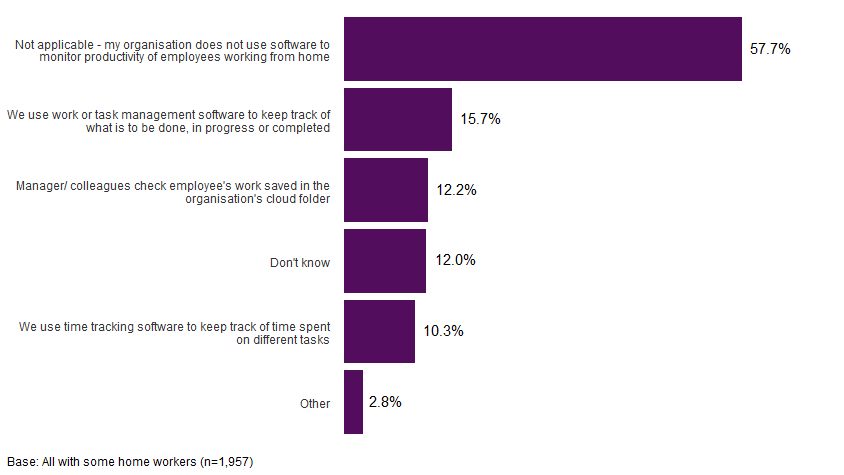

We then asked the bosses with regular home workers about the types of software used to measure their productivity (Figure 3):

Figure 3: What types of software are used to measure your people’s productivity when they are working from home?

Interestingly, bosses at organisations that use one or more types of software to monitor the performance of home workers were more likely to find the measures listed in Figure 1 acceptable. Among those at organisations that use task management software, time tracking software or check employees’ work in cloud folders, four-fifths (81.6%) agreed with the measures in Figure 1. But only half agreed (47.0%) with this among those that come from organisations that don’t use software to monitor productivity.

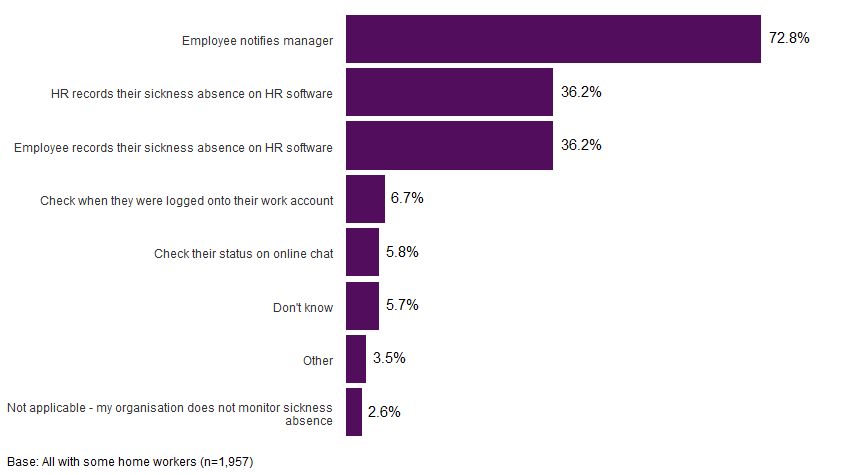

Notifying the manager or recording sickness absences on HR software are common ways of keeping track of sickness absence for homeworking employees (Figure 4). This practice is no different to what we would expect for employees who work onsite.

Figure 4: How does your organisation monitor their sickness absence?

Much has been written about monitoring and surveillance of people at work. Debates and ‘big brother’ stories on the subject appear often in the media. The rise of hybrid working, along with increased capability to monitor electronically as work becomes more digitised, have fuelled the continued debate on acceptable monitoring practices.

What’s clear is that many people are uneasy about increased monitoring at work. The majority (88%) of managers and workers who responded to an earlier CIPD survey agreed that increased workplace monitoring has more downsides than benefits. And almost three-quarters (73%) said that introducing new technologies in the workplace will damage trust between workers and employers.

In the same vein, a Trade Union Congress survey found that two-thirds of workers (66%) are concerned that workplace monitoring could be used in a discriminatory way if left unregulated. The TUC has called for rights for individuals to control what personal data employers collect on them. An academic report published by the European Union in 2021 noted that the monitoring of remote workers intensified over COVID-19, and provided recommendations to mitigate the psychosocial risks.

Yet when it comes to acceptable monitoring practices, most of what has been published are guidance and opinion pieces from individuals. Our findings fill some of the insight gaps by investigating what more than 2,000 UK bosses think are acceptable monitoring practices for remote workers and what’s practiced in their organisations. We found that opinions of what’s acceptable is influenced by management level, percentage of hybrid workers, and whether similar monitoring practices already exist in their organisations. We also saw that bosses are uncomfortable with collecting more personal information than is necessary for monitoring their people’s performance and wellbeing.

From a resource perspective, justification for the money and time invested should be tied to what you want to achieve. Is the monitoring needed for auditing, security or legal purposes? What are the critical checkpoints? What is the least intrusive and least resource intensive approach that fit you and your people?

If you need to introduce new a monitoring measure:

See our partner HiBob’s blogs for tips on keeping dispersed teams engaged and building cultures of authenticity and empathy, and a Hibob employee’s view of what makes them want to stay at the company.

In the next article, we’ll look at the three-year software investment plans of HR bosses within the context of their organisation’s business focus.

Browse our A–Z catalogue of information, guidance and resources covering all aspects of people practice.

Discover our practice guidance and recommendations to tackle bullying and harassment in the workplace.

Hayfa joined us in 2020. Hayfa has degrees in computer science and human resources from University of York and University of Warwick respectively.

She started her career in the private sector working in IT and then HR and has been writing for the HR community since 2012. Previously she worked for another membership organisation (UCEA) where she expanded the range of pay and workforce benchmarking data available to the higher education HR community.

She is interested in how the people profession can contribute to good work through technology and has written several publications on our behalf, as well as judging our people management awards, speaking at conferences and exhibitions and providing commentary to the media on the subjects of people and technology.

An overview of the purpose and benefits of HR policies and how to implement and communicate them effectively throughout an organisation

Listen to our new fortnightly podcast providing expert insights from HR leaders on the topical issues impacting the world of work

Listen now

Learn how non-executive directors (NEDs) differ from executive directors and how they operate within an organisation

This factsheet explores corporate responsibility and putting it into action in the workplace

Monthly round-up of changes in employment law in the UK

Research on how an employee's socioeconomic background or class affects their development opportunities and how to maximise social mobility in the workplace

We look at the main focus areas and share practical examples from organisations who are optimising their HR operating model

Ben Willmott explores the new Labour Government strategies to enhance skills and employment to boost economic growth