The true story of the UK gig economy

James Cockett discusses the key findings and insights from our report on the UK gig economy

James Cockett discusses the key findings and insights from our report on the UK gig economy

“How big is the gig economy in the UK? In what type of jobs do people work? Who is more dependent on the gig economy?” These were three questions put to me by a colleague several months ago. The answer was far from straightforward – a web search led to a wide range of estimates. A freedom of information (FOI) request to the Office for National Statistics in 2021 alludes to why: because “there is no formal agreed definition of what does or does not constitute a gig economy worker. Consequently, there are no official statistics relating to the number of gig economy workers.”

In 2017, the CIPD released a report on the experiences of those in the gig economy. The report defined the gig economy as “participants who trade their time and skills through online platforms (websites or apps), providing a service to a third party as a form of paid employment.” This is the UK Government’s working definition.

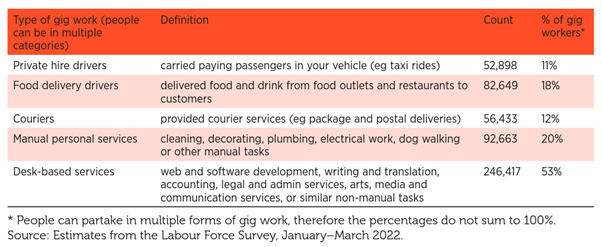

In September 2023, the CIPD released a report with new estimates on the gig economy with data from the Labour Force Survey (LFS). Respondents were asked: “thinking about the past three months, what have you done to earn money using third-party websites, apps, or online platforms?” This was followed by a series of descriptions of the types of roles in the gig economy (defined in Table 1). This was akin to our previous research noted above.

Our analysis showed the gig economy in the UK was estimated at just under half a million people (463,583). In a labour force of over 32.5 million, workers in the gig economy make up just 1.4% of total employment.

This is in stark contrast to TUC research in 2021 which found that 14.7% of working people, estimated at 4.4 million people, were working for gig economy platforms at least once a week in England and Wales. This, however, was based on a survey of just 2,201 participants.

A common perception is that most people working in the gig economy are private hire drivers or food delivery drivers due to visible presence of big players such as Uber, Deliveroo or Just Eat. Our estimates show just over 50,000 people work as private hire drivers, one in ten of those working in the gig economy. Despite more undertaking food delivery (just over 80,000), they still make up only a fifth of the total.

By contrast, a quarter of a million people undertake desk-based services such as web development or translation and legal services, through apps and websites. These people make up over half of the UK gig economy. Nearly 100,000 people undertake cleaning, decorating, plumbing, electrical work, dog walking or other manual tasks in the gig economy.

Size of employment in the UK, in each type of gig work

Our report highlights two groups to be more reliant on gig economy work for their income: ethnic minorities and people with disabilities. Lower barriers to entry in the gig economy may be a considerable factor as to why they enter the gig economy. However, the higher dependency may also indicate they are unable to access secure, permanent employment and are facing barriers to equal opportunity in the labour market.

UK gig workers who see gig work as their main source of income, by gender, ethnicity and disability status (%)

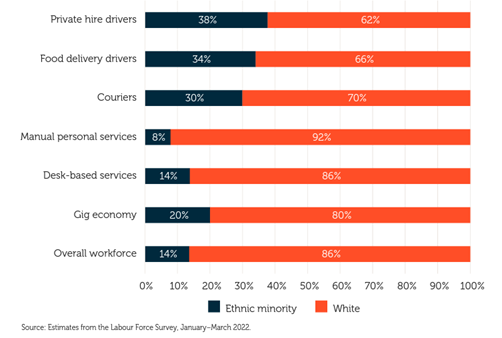

We found that a quarter (24.8%) of all UK gig economy workers were based in London, where almost half of the population (46%) have an ethnic minority background. Twenty-nine percent of the population in major urban conurbations in England were also ethnic minorities. It is therefore unsurprising that the gig economy is overrepresented by ethnic minorities (20% vs 14% in the wider workforce), and that over a third of food delivery drivers and 38% percent of private hire drivers have an ethnic minority background.

Ethnicity breakdown, by type of UK gig work (%)

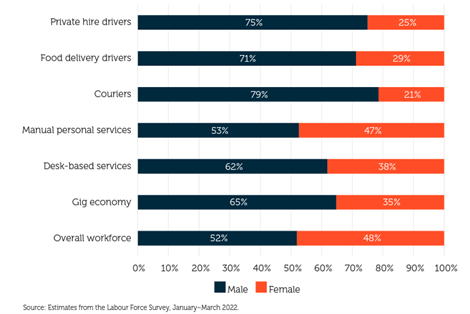

As well as being overrepresented by ethnic minorities, all transportation gig economy roles were overrepresented by men. More than seven in ten private hire drivers (75%), food delivery drivers (71%) and couriers (79%) are men. Combining this with the other roles in gig economy, we found 65% of participants in the gig economy were men.

Gender breakdown, by type of UK gig work (%)

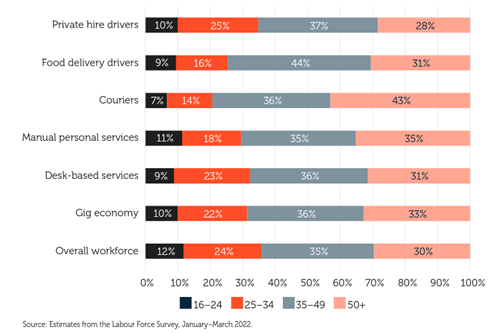

While on a recent visit to Deliveroo, the UK Work and Pensions Secretary said the gig economy offers “great opportunities” and that it was “good for people to consider options they might not have otherwise thought of”, in reference to older workers. Our analysis shows that those aged 50+ were prevalent in almost all types of gig work at a higher rate than in the wider workforce. Unlike previous research, which found nearly a third of the gig economy was aged 16-24, we found that participation in the gig economy was not a phenomenon among young people. Those aged 16-24 make up 10% of all gig workers, lower than the 12% in the wider workforce.

Age breakdown, by type of UK gig work (%)

The gig economy displays significant heterogeneity. While the flexibility and earning potential may be good for some, the instability of income and precarious nature of work for others remains a concern. In light of this, we provide recommendations for policy-makers on how to improve employment conditions for those working in the gig economy.

Browse our A–Z catalogue of information, guidance and resources covering all aspects of people practice.

Discover our practice guidance and recommendations to tackle bullying and harassment in the workplace.

Practical guidance to help you identify and implement good atypical working practices

Explore the CIPD’s point of view on employment status, rights and regulation, including recommendations for employers and actions for the UK Government

Understand how being defined in UK law as an employee, a worker or self-employed affects employment rights and employers’ legal responsibilities

Explore our collection of resources around legal issues surrounding employees and workers, including Q&As for various types of workers and relevant case law

Monthly round-up of changes in employment law in the UK

Research on how an employee's socioeconomic background or class affects their development opportunities and how to maximise social mobility in the workplace

We look at the main focus areas and share practical examples from organisations who are optimising their HR operating model

Ben Willmott explores the new Labour Government strategies to enhance skills and employment to boost economic growth