Flexible working arrangements and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

Data shows a drop in all forms of flexible working arrangements - other than homeworking - since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic

Data shows a drop in all forms of flexible working arrangements - other than homeworking - since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic

More action is needed to increase the uptake of flexible working arrangements, as data shows a drop in all forms of flexible working arrangements (other than homeworking) since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. CIPD research suggests that UK workers face inequality due to a stark difference in employers offering flexible working practices, with just under half (46%) of employees saying they do not have flexible working arrangements in their current role.

The CIPD’s view is that flexible working practices should be the norm – not the exception – for all UK workers. With that in mind, our #FlexFrom1st campaign encourages employers to support flexible working for all and the right to request flexible working from day one of employment. We're also calling for a change to UK law to make flexible working requests a day one right for all employees.

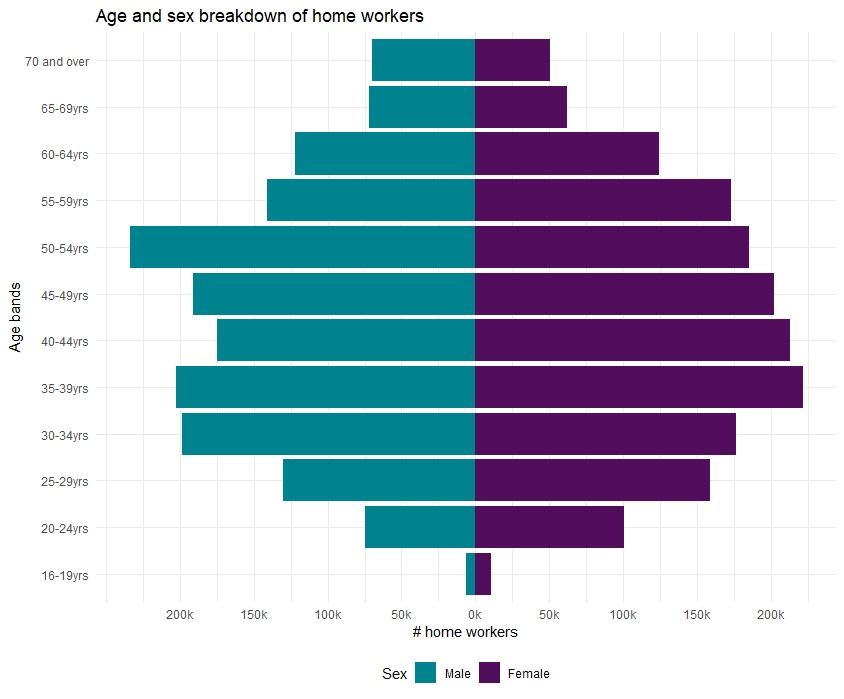

Our examination of the Labour Force Survey (of 74,832 people in Oct–Dec 2020)₁(the most up to date evidence) reveals the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on flexible working arrangements. Unsurprisingly, there's been a substantial increase in homeworking during this period. Back in 2010 there were around 3% of workers working from home all the time. That figure was rising gradually to around 5% in January–March 2020, before the impact of the pandemic. However, after that point, the figures then rose rapidly in response to the UK Government’s guidance that all workers (who were able to) should work from home. In Oct–Dec 2020, the number working from home all the time was at 10%.

We identified home workers as those responding ‘own home’ to the question ‘HOME – Whether working from home in main job’. Less conservative estimates sometimes include ‘In the same grounds or buildings as home’ and ‘In different places using home as a base’, which will give larger numbers.

While homeworking is split fairly evenly between the sexes, those working in professional occupations were most likely to work from home all the time and particularly those in professional, scientific and technical roles, information and communication and financial and insurance. Unsurprisingly, those least likely to work from home all the time were in mining and quarrying, water supply, sewerage and waste and electricity, gas and air conditioning supply roles.

What is more surprising, and concerning, is that the data shows a drop in all other forms of flexible working arrangements since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Across the board, the number of workers in a job-share, working flexi-time, compressed hours, part-time hours, term-time working, annualised hours and zero-hour contracts has reduced significantly since the start of the pandemic.

|

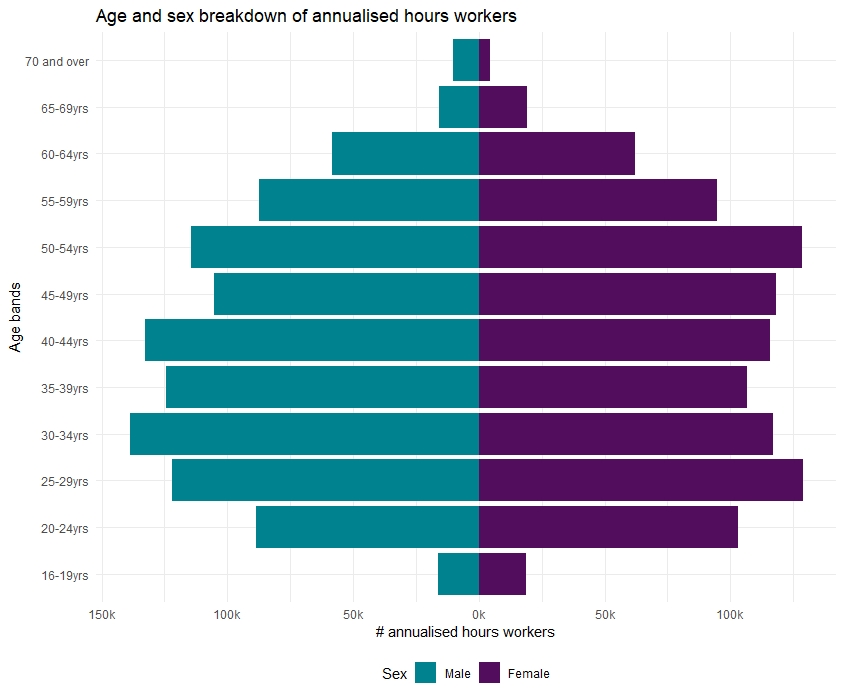

Annualised hoursUnder this arrangement a worker has a set number of hours within the year but may work more or less on a given week in order to meet demand. 6.3% of workers work annualised hours with a relatively even spread between age groups and genders. The download here shows more detail. |

|

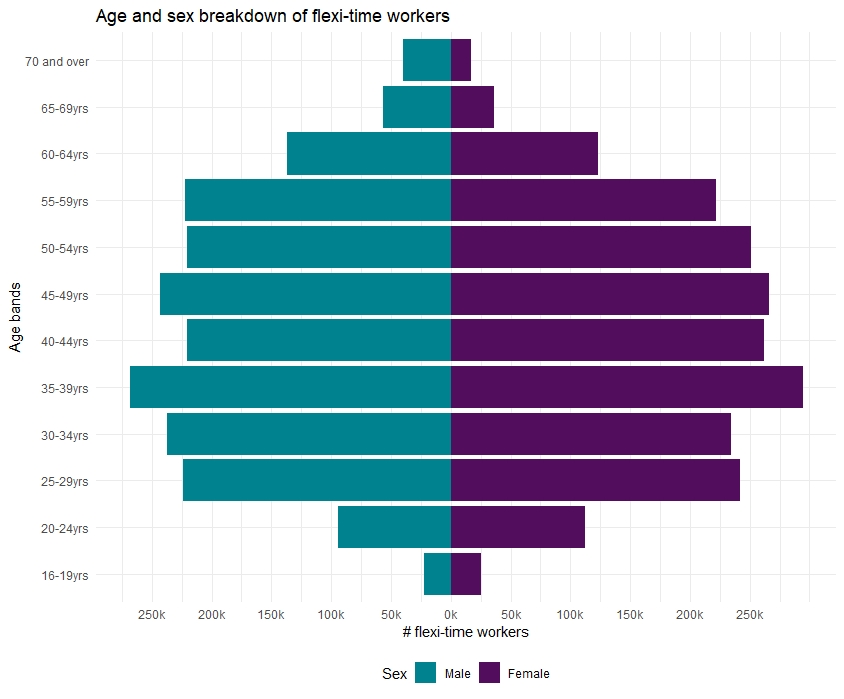

Flexi-time workingFlexi-time offers workers the chance to decide the start and end times of their day as well as their breaks though often within certain limits. 12.6% of workers use flexi−time with a relatively even spread between age groups and genders. The download here shows more detail. |

|

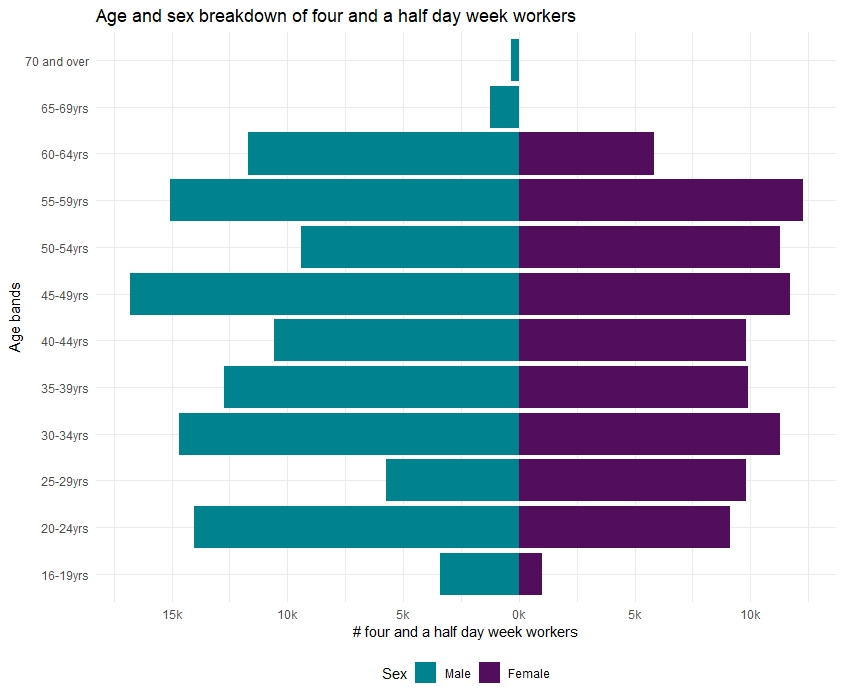

Four and a half day week workersThe ONS define this type of working as “typically involving the normal working week finishing early on Fridays. The short day need not necessarily be Friday, but this is the most obvious and common day. This working pattern is full-time with compressed hours”. This is not a very common policy and only 0.6% of workers work this type of arrangement. The download here shows more detail. |

|

Home workersThere are various definitions of homeworking but in this instance, we have used a strict definition in which the job is based at home. During the pandemic this rose to around 10.2% of workers. Homeworkers tend to be older. The download here shows more detail. |

|

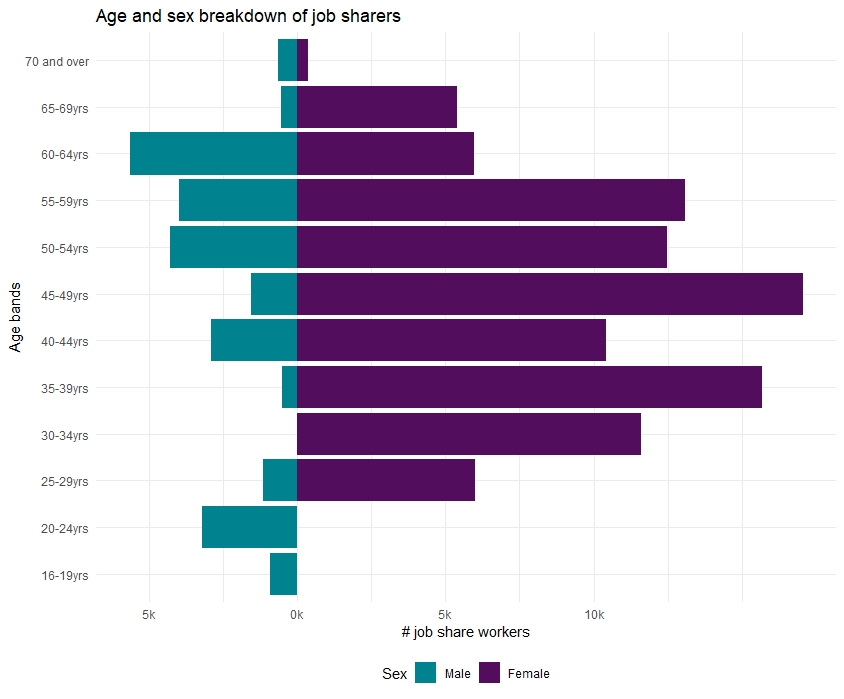

Job sharersThe ONS define job sharing as “a type of part-time working. A full-time job is divided between, usually, two people. The job sharers work at different times, although there may be a changeover period.” Only 0.4% of workers work this type of arrangement and the vast majority of these are women. The download here shows more detail. |

|

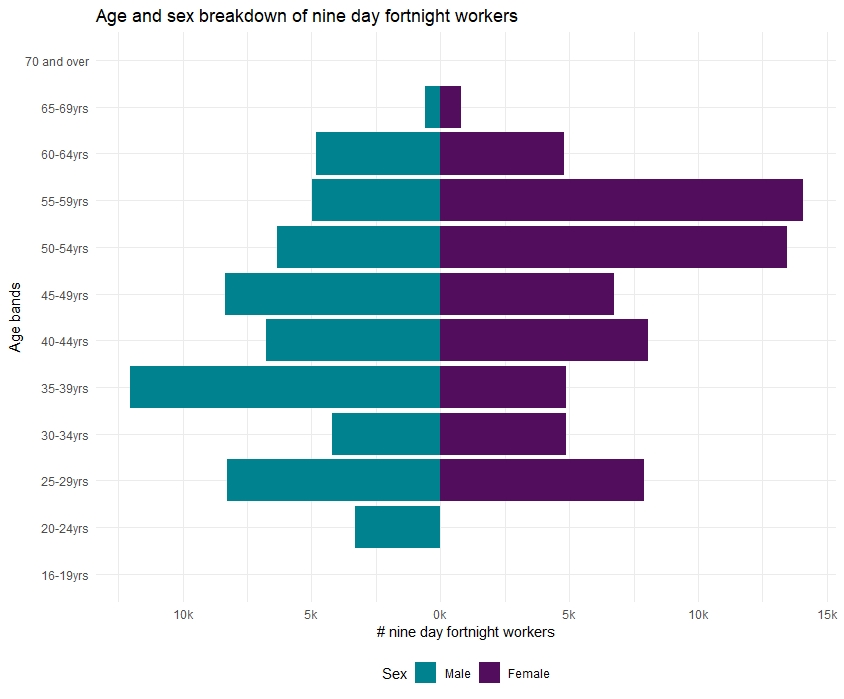

Nine day fortnight workersThe ONS define this way of working as follows: “In this pattern, individual employees have one day off every other week. The actual day off may vary so long as the employee keeps to an alternating pattern of one 5-day week followed by one 4-day week. This working pattern is full-time with compressed hours.” It is not a very common policy and only 0.4% work this type of arrangement. The download here shows more detail. |

|

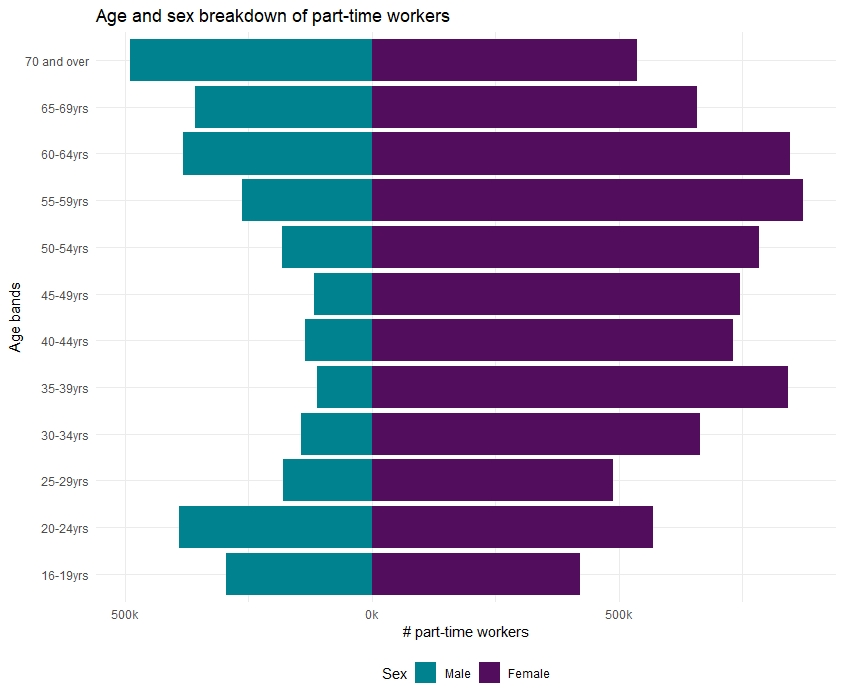

Part-time workersAs the name implies, part time workers work a fraction of the hours of a full-time worker. This is the most popular form of flexible working. 27.6% of workers are part-time and this group is largely female. The download here shows more detail. |

|

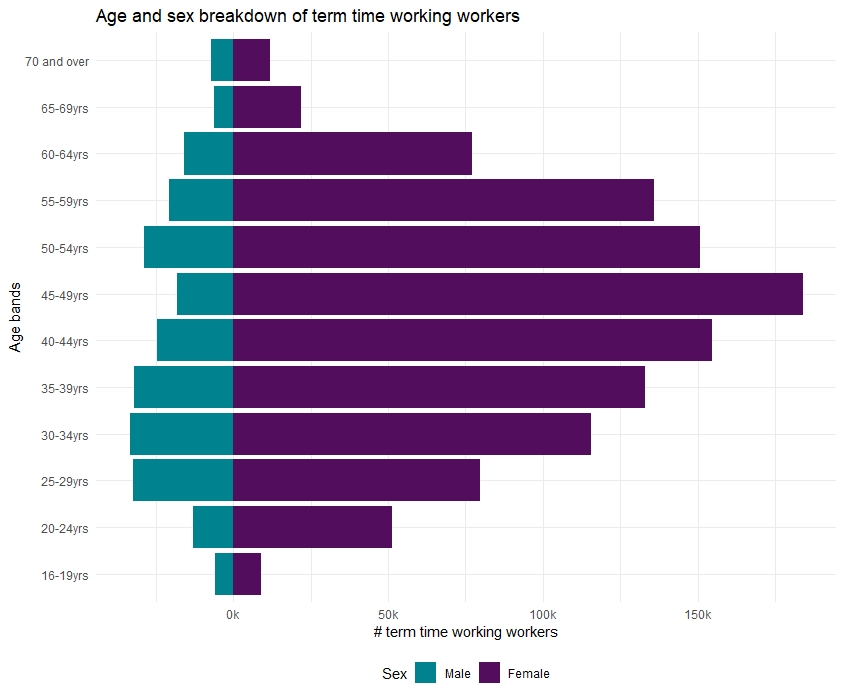

Term-time workingThe ONS defines term time working as follows: “Employees’ work during the school or college term. Unpaid leave is taken during the school holidays, although their pay may be spread equally over the year.” 4.2% of workers have a term time working arrangement. Unsurprisingly the vast majority of these work in the education sector and are women. The download here shows more detail. |

|

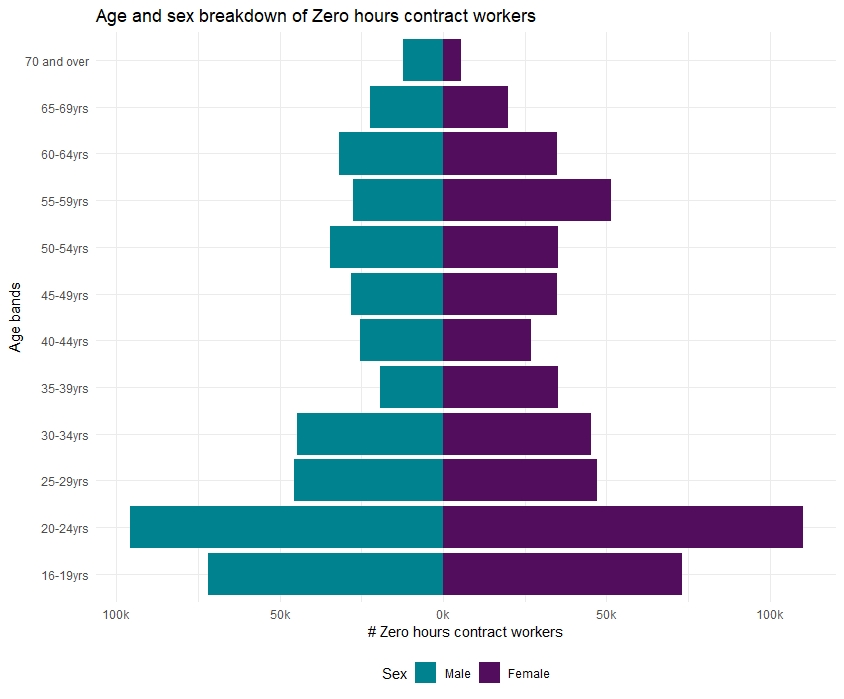

Zero hours contractsUnder this arrangement a worker does not have a fixed number of hours. Despite plenty of media attention this type of working arrangement only accounts for 3% of workers. Younger workers are most likely to work this type of arrangement and hospitality is the industry with the highest number of these workers. The download here shows more detail. |

Table 1: Prevalence/uptake of flexible working practices before the full impact of the pandemic and after

CIPD survey data shows a real unmet demand around flexible working arrangements. This finding is corroborated by the Labour Force Survey, which finds that 9.3% of workers – equivalent to 3 million people – said they would prefer to work shorter hours and accept the cut in pay that comes with this. This finding suggests that for many, the 9-to-5 working day is too rigid, and policies such as flexi-time (flexible start and finish times), compressed hours and part-time hours would better match peoples’ preferences.

We can see in the table above, the proportion of workers on compressed hours (either a 9-day fortnight or 4-and-a-half-day week) is particularly low. There is real potential to increase this type of flexible working, in line with worker expectations. Doing so could also boost employer agility and help to enhance customer/ client response times.

The proportion working a job-share is also currently very small (about 1 in every 200 workers) with very few in senior positions. This seems like a missed opportunity. For employees, job shares can often facilitate progression, and the ability to balance personal commitments. Employers can benefit from two sets of skills, knowledge and experience.

Now is the time for organisations to increase their flexible working offerings not pull back. The CIPD encourages organisations to collaborate with their employees to find flexible solutions that are mutually beneficial.

While many see the pandemic as a driver of flexible working practices, particularly around home working, the reality for many is very different. We need a new understanding of what flexible working is, and we need employers to embrace flexible working arrangements beyond home working, to give opportunity and choice to all. Employees may not always be able to change where they work, but they should have more choice and a say in when and how they work.

Having the ability to build in flexible working arrangements, such as changes to hours, term-time working or job shares, will empower people to have greater control and flexibility in their working life. This is good for inclusion and opening up opportunities to people who have other constraints in being able to work standard-hour weeks or in getting to a place of work. It also supports peoples’ wellbeing and productivity. Fairness of opportunity in working flexibly ensures organisations do not end up with divisions or a two-tier workforce.

₁ For all cross-sectional cuts, the latest available labour force survey (Oct-Dec 2020) was used. All time series LFS quarterly datasets are clearly labelled on the x axis: Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA), Office for National Statistics, Social Survey Division, 2021, Quarterly Labour Force Survey, October– December, 2020, [data collection], UK Data Service, 2nd Edition, Accessed 25 March 2021. SN: 8777.

Tackling barriers to work today whilst creating inclusive workplaces of tomorrow.

Discover our practice guidance and recommendations to tackle bullying and harassment in the workplace.

A Northern Ireland summary of the CIPD Good Work Index 2024 survey report

A Northern Ireland summary of the CIPD Good Work Index 2024 survey report

Dedicated analysis of job quality and its impact on working lives in Scotland

A North of England summary of the CIPD Good Work Index 2024 survey report