Where have all the workers gone?

Jon Boys reflects on his recent appearance in front of the House of Lords Economic Affairs Committee, where he presented his evidence to answer the question: ‘where have all the workers gone?’

Jon Boys reflects on his recent appearance in front of the House of Lords Economic Affairs Committee, where he presented his evidence to answer the question: ‘where have all the workers gone?’

I recently gave evidence to a Lords economic affairs committee on ‘where have all the workers gone?’ It’s a good question and one the HR profession is grappling with.

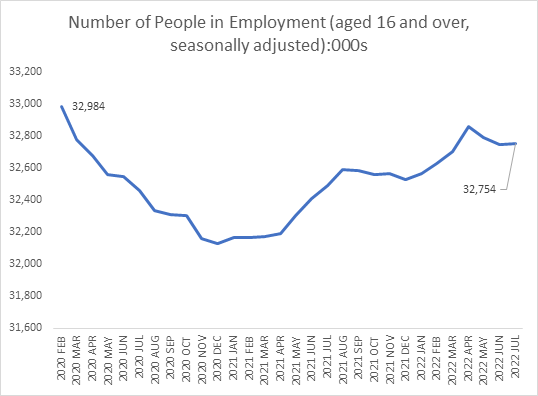

The real problem is the imbalance between the demand for labour and the supply. Demand for labour remains near record high levels as evidenced by the high number of job vacancies currently being advertised. The supply of workers is restricted for a few reasons. The unemployment rate – at 3.5% - is the lowest for 50 years. To be unemployed someone must be seeking and available to work. If unemployment is low, and employment remains lower than pre-pandemic then there must be a third place that workers have moved to. That place is called inactivity and it includes students, retirees, and the long-term sick.

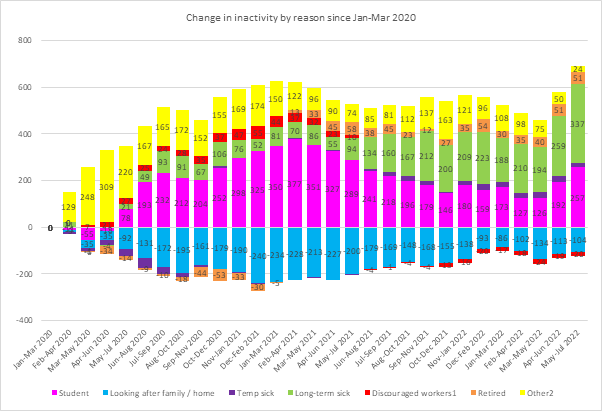

Looking at the change in numbers for these inactive categories since the beginning of the pandemic, it is clear that students increased. This was perhaps a sensible strategy when job opportunities were lower during the pandemic. The more worrying trend is the increasing numbers of long-term sick. This could be a combination of long Covid, NHS waiting lists, and perhaps demographics too as the population is ageing.

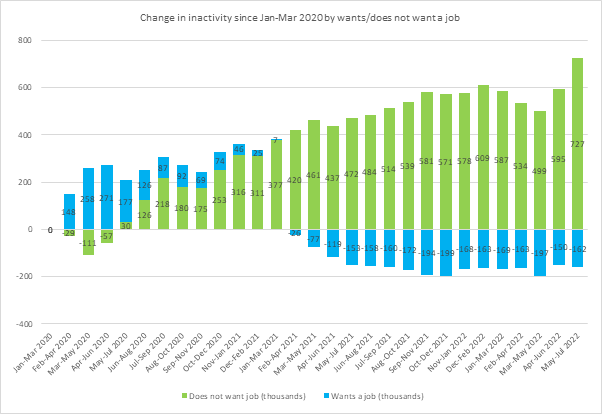

Another way of cutting the inactive group is to look at those who say they would like a job vs those who say they do not want to work. The entire increase in inactivity can be attributed to those not wanting to work. This means that efforts to reverse the trend will be working against a gradient.

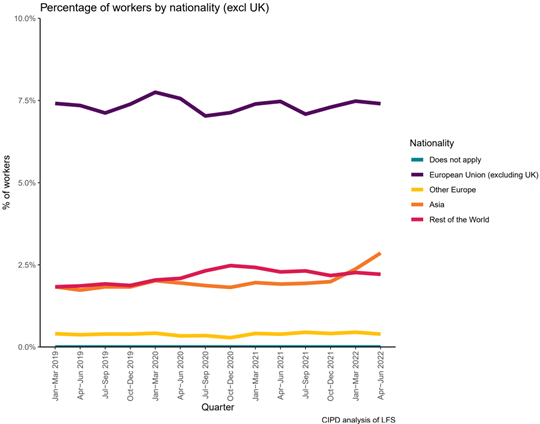

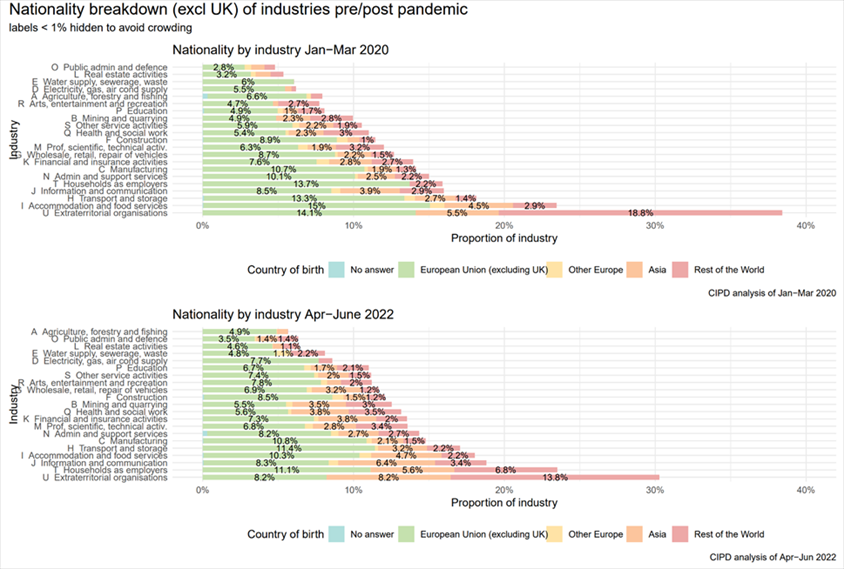

Due to problems collecting data during the pandemic, it has been difficult to know the effect of immigration on the workforce. EU nationals remain the largest group (outside of UK nationals) in the labour market but nationals of Asian countries are rising as a proportion of the workforce.

Looking at a breakdown by industry, pre and post-pandemic, some sectors are much more reliant on foreign nationals than others. The hospitality sector (accommodation and food services) has gone from 15% EU national to 10.3% when comparing pre and post-pandemic quarters.

Employers can focus on job quality to entice people back. The CIPD’s labour market outlook shows that employers are increasingly responding to recruitment and retention difficulties with things such as advertising more jobs as flexible (35%).

The UK clearly has a problem with long-term sickness and employers and policymakers need to take this more seriously. Significantly improving access to occupational health services for workers and advice and support for employers on occupational health issues affecting staff could have a big impact over time. The provision of timely access to occupational health services to workers in their 20s and 30s who suffer from back pain or other musculoskeletal problems would mean that steps can be taken to reduce the likelihood of these conditions becoming chronic, affecting people’s health and their ability to work.

On immigration, expanding the shortage occupation list could further boost the labour supply.

Today there is an imperative to boost labour supply as it is acting as a constraint on growth. This may not be the case tomorrow. If the UK enters a downturn and unemployment increases as most forecasts expect to happen, the demand for labour will reduce and the effect of acute shortages currently experienced will lessen. However, longer term, creating good quality work that caters to a wide variety of peoples’ preferences and needs will make UK employers more resilient.

Browse our A–Z catalogue of information, guidance and resources covering all aspects of people practice.

Discover our practice guidance and recommendations to tackle bullying and harassment in the workplace.

Jon joined the CIPD in January 2019 as an Economist. He is an experienced labour market analyst with expertise in pay and conditions, education and skills, and productivity.

Jon primarily uses quantitative techniques to uncover insights in labour market data, both publicly available and generated through in house surveying. Jon regularly contributes commentary and analysis of economic issues on the world of work to online, print and TV media. Recent work includes the creation of an international ranking of work quality, analysis of firm level gender pay gap reporting data, and an ongoing programme of work looking at the changing age profile of the UK workforce.

Research on how an employee's socioeconomic background or class affects their development opportunities and how to maximise social mobility in the workplace

We outline the challenges impacting job quality in Scotland as revealed in the CIPD's Working Lives Scotland 2024 report

Marek Zemanik analyses the CIPD’s newly published Working Lives Scotland 2023 report

How much difference does people management quality make when it comes to being a good boss? Mark Beatson reviews this question by drawing on the CIPD’s recent report, ‘The importance of people management: Analysis of its impact on employees’

Monthly round-up of changes in employment law in the UK

Research on how an employee's socioeconomic background or class affects their development opportunities and how to maximise social mobility in the workplace

We look at the main focus areas and share practical examples from organisations who are optimising their HR operating model

Ben Willmott explores the new Labour Government strategies to enhance skills and employment to boost economic growth