Could mismatch in desired and actual hours worked prompt early labour market exit?

We examine people’s desired hours and how this compares to the hours they actually work

We examine people’s desired hours and how this compares to the hours they actually work

A mismatch between the hours people want to work and their actual hours may be a contributing factor to the early labour market exit of older workers. Thus, any response from employers and the government that could reduce the mismatch should be considered.

The analysis was based on questions in the UK Labour Force Survey asking whether the respondent:

From this combination we derive five mutually exclusive response categories:

Much has been written about early exit from the labour market and the need to extend working lives. The subject garnered increased attention post-COVID when many older workers left work and did not return. With rising life expectancy and pressure on public services, people will have to work for longer than in the past. Given low unemployment and high rates of economic inactivity restricting workforce size, there is a business case to helping people work longer.

Organisations increasingly recognise the valuable skills and experience that over-50s bring to the workplace and the importance of providing opportunities to this demographic to have meaningful work that not only supports their financial security, but is also good for wellbeing and sense of purpose. There are likely many causes of early exit and therefore a myriad of solutions for extending working lives.

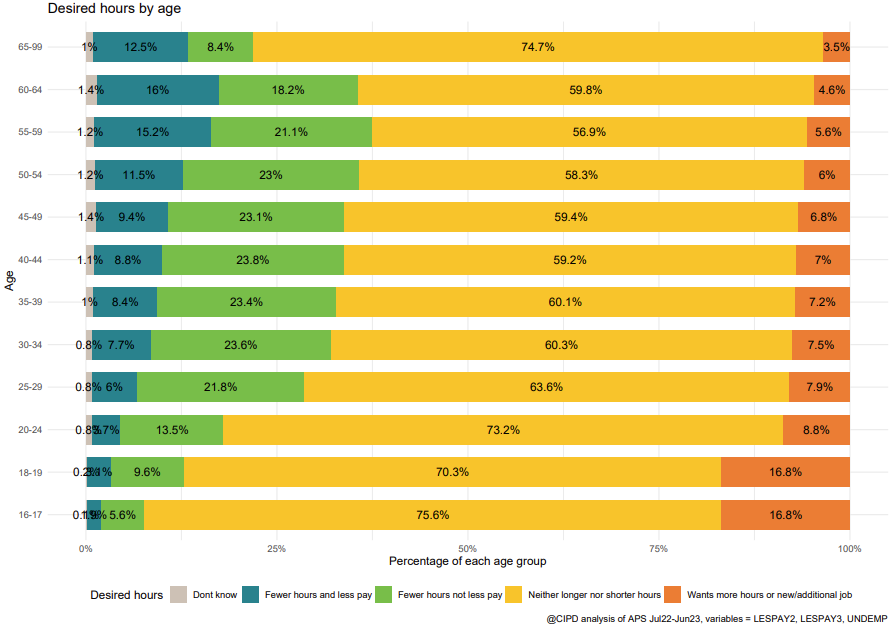

The proportion of people who would like fewer hours and are happy to take a pay cut to do so increases with age (until 65+ at which point very few people are working and those that do, probably do so more on their own terms). If we include those who want to reduce hours but don’t want a pay cut, we get a third of older workers. The problem is we may be presenting older workers with a binary option - work too much and be unhappy, or retire early and don’t work at all. The third way is obviously to have more part-time working and phased retirement options making exit from work less of a cliff edge.

What’s interesting about the graph is that it shows the residual unhappiness. Many people can and do reduce their hours or retire early. With this in mind it is surprising that the figures are so high.

From 6 April, all employees will have the right to request flexible working from day one. This will affect few older workers, most of whom have significantly longer tenure and already have the right to request. However, having the right and using it are two different things. It may simply be that there is a status quo bias and norm towards a pattern of work that doesn’t serve the needs of older workers.

Nobel Prize winning economist Claudia Goldin came up with the concept of ‘greedy jobs’. These are big jobs, that take a lot from people in terms of time and energy but pay disproportionately well. In these jobs the pay increases with the hours worked (not linearly as with a wage rate, but disproportionately – that is to say, they reward long hours). Goldin suggest we need more flexibility in these jobs. This may make those doing the jobs happier, but also tempt those who have self-selected out of doing them, into doing them.

Though legislation is important, we must also work to change norms around flexibility. There is a business case to be made for flexibility, if the alternative is to lose (much needed) workers sooner than they might otherwise leave.

Jon s an experienced labour market analyst with expertise in pay and conditions, education and skills, and productivity.

Jon used quantitative techniques to uncover insights in labour market data, both publicly available and generated through CIPD surveys.

Stay up to date with the latest recruitment and redundancy trends in the UK.

Discover how the CIPD and the Institute for the Future of Work are supporting organisations in understanding how to take a people-centred approach to integrate AI-enabled solutions effectively and responsibly at work

Find out what people professionals said about their working lives and career development prospects in our recent pulse survey

As artificial intelligence continues its rapid advancement and becomes the much touted focus for investment and development, we highlight the critical role of the people profession and explain how the CIPD and its members will be involved shaping its impact at work

A look at whether artificial intelligence can cover skills shortages by exploring the benefits of AI and the advantages that can be gained by using generative AI such as ChatGPT