Better work, better care?

Mark Beatson’s article discusses the issues that employees in the social care sector are facing

Mark Beatson’s article discusses the issues that employees in the social care sector are facing

The UK Government’s social care White Paper, finally published late last year, was widely criticised for failing to give enough weight to the workforce aspects. Put bluntly, too much on how to pay for care and not enough on who will do it.

Even the UK Government's evidence paper couldn’t ignore the issues: large numbers of unfilled vacancies in the sector and high rates of staff turnover. This has consequences for the quality of care provided. According to Skills for Care, care providers with high staff turnover also have lower ratings for quality of care. However, population ageing means the demand for social care – and those to provide it – is likely to increase over time. If the sector fails to attract and retain recruits, debates about who pays, and how much, risk being academic.

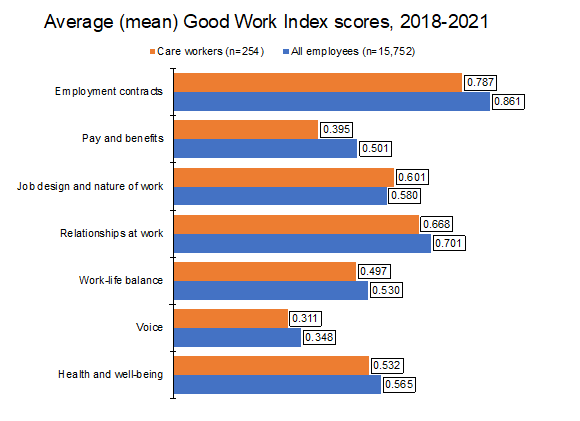

The quality of work is central to recruitment and retention. Happily, CIPD has a tool – the Good Work Index (GWI) – capable of providing a rounded perspective on quality of work issues. By combining data from four years’ surveys, we can drill down and compare the quality of work of front-line care workers against that of all employees.

The chart below provides an overview based on average GWI scores. It shows there are two dimensions of job quality where care work compares particularly unfavourably with other jobs – employment contracts and pay and benefits.

Further analysis shows there are two underlying problems with care work, problems that the White Paper failed to address.

Problem 1: Low pay

Nearly half (46%) of employees agree that their pay is reasonable given their skills and experience. Among care workers, though, the proportion is just 34%.

This problem is not new. The Low Pay Commission has repeatedly drawn attention to the way that the arrangements for financing social care act as a brake on the ability of private care providers to raise hourly wage rates.

Problem 2: Underemployment

Underemployment is when (paid) hours worked are less than the number of hours the worker would like to work (and be paid for). While 14% of employees said they were underemployed, the rate among care workers was 23%.

In addition, there is anecdotal evidence that care workers may not always be paid for the hours they do work, especially in domiciliary (home-based) care. For example, financial pressures may mean that a local authority only pays a care provider to deliver a short, discrete block of care (15 or 30 minutes, say). The care provider transmits this limited commitment onto the care worker through a time-limited booking. If the care episode takes longer than anticipated, the risk of non-payment for this extra time is often borne by the individual care worker. Qualitative research suggests it is practices like these that care workers find especially irksome and may well motivate a lot of staff turnover as care workers look for other jobs in the care sector that they think will take less advantage of their dedication and goodwill.

Job satisfaction among care workers is 60%, which is slightly lower than for all employees (65%) but may not be a statistically significant difference.

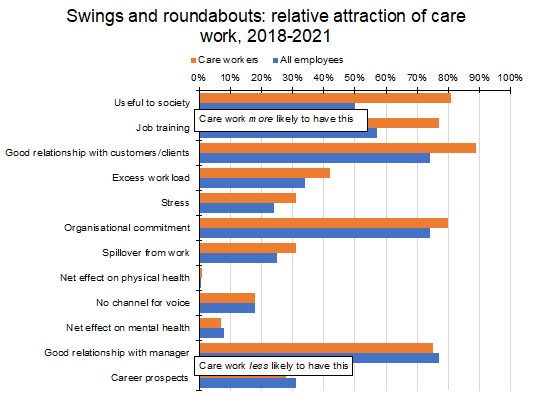

Given the problematic aspects of care work, there must be parts of it that employees find more agreeable. And there are. The chart below shows highlighted survey findings, especially for those areas where care work over- and under-performs.

Source: CIPD/YouGov UK Working Lives surveys.

Care workers think what they do matters: 50% of employees think their job is useful to society, 81% of care workers think so. In addition, care workers are much more likely to think they are given the training needed to do their job than other employees – even if their career prospects aren’t great. And care workers are more likely to say they have a good (or better) relationship with customers and clients.

Against this, the work is clearly hard in terms of workload and impact on family life.

Our analysis looks at all jobs and all employees. Obviously, there are good and bad jobs. And how any job is seen by the employee holding it will depend on their circumstances and disposition. Within social care, quality of work pressures are greatest on independent care providers and those providing domiciliary care.

This also explains why some factors appear unimportant - in particular, the quality of line management. Other, unconnected work suggests that the quality of line management (as judged by the employee) is connected to employee performance and wellbeing. It probably does for care work as well. However, care workers gave their line managers a similar average rating as other employees. Although the quality of line management is always an issue, there is no evidence of it being especially problematic in care work.

Minimum employment standards, like minimum wages, can help ensure that bad jobs don’t become too bad. However, when minimum standards become engrained, as they have in social care, their effectiveness in signalling job quality is arguably diminished and we see excessive staff turnover as workers seek out jobs that are not quite as bad/a little better.

More money going into social care may well help to ease the quality of work concerns. A lot of the problems with pay and hours could be reduced simply by easing the financial pressure on local authorities and care providers.

The challenge for the government is ensuring more money gets into social care in the first place. The government has made it clear that tackling NHS backlogs gets priority. Given the possibility of backlogs persisting, as well as ever-increasing demand for healthcare, will there ever be enough left for social care? Far from a once-and-for-all “fix”, difficult decisions may simply have been postponed until future spending reviews.

Browse our A–Z catalogue of information, guidance and resources covering all aspects of people practice.

Discover our practice guidance and recommendations to tackle bullying and harassment in the workplace.

Mark's respected labour market analysis and commentary strengthens the CIPD’s ability to lead thinking and influence policy making across the whole spectrum of people management and workplace issues.

Prior to joining the CIPD, Mark was an economic consultant and for over 20 years worked as an economist in the Civil Service, latterly at Chief Economist/Director level, in a range of Government departments including the Department for Business Innovation and Skills (BIS), the Department for Innovation, Universities and Skills (DIUS), the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) and HM Treasury.

Research on how an employee's socioeconomic background or class affects their development opportunities and how to maximise social mobility in the workplace

What are the barriers that stand in the way of achieving 'good work', and which need to be addressed as a priority?

Listen now

A Northern Ireland summary of the CIPD Good Work Index 2024 survey report

Monthly round-up of changes in employment law in the UK

Research on how an employee's socioeconomic background or class affects their development opportunities and how to maximise social mobility in the workplace

We look at the main focus areas and share practical examples from organisations who are optimising their HR operating model

Ben Willmott explores the new Labour Government strategies to enhance skills and employment to boost economic growth